The problem of a performance artist’s legacy is not limited to the solo artist whose biography and distinctive persona are central to their work. As discussed in my last essay these performances cannot be recreated or performed by anyone else after the individual artist’s demise, without becoming mere impersonations. Thus they survive solely as documentation in film, video, or audio recording, and if text-based on the printed page. The auteur interdisciplinary performing artist faces similar difficulties when her work is distinguished by a specific visual aesthetic that expresses the philosophical core of the work as represented not only by the music, libretto, choreography and thematic content, but the character and style of the auteur as a charismatic performer as well.

How does the auteur artist ensure the authenticity, meaning and purpose of the original for the future? And what happens when a director and/or producer with a markedly different aesthetic stages the work? Clearly it is not the same work. Whether only the musical composition, or in some instances the story line, be retained as the foundation of the work, something essential will be lost in translation. When another artist or director imposes his or her own vision, aesthetic sensibility, interpretation and intent onto the new production it is no longer the work of the auteur.

There are many examples of this in cinema when Hollywood remakes a classic auteur foreign film such as Andrei Tarkovsky’s meditative science fiction masterpiece Solaris (1972) based on a novel by Stanislaw Lem. A deeply psychological exploration that takes place on an old Soviet scientific research station orbiting a mysterious alien planet, Tarkovsky’s film is a long, slow hallucinogenic and metaphysical excursion into the dark recesses of the psyche and its capacity to comprehend the unknowable. Whereas Steven Soderbergh’s 2002 remake is a more accessible, plot-driven glossy American version produced by James Cameron, starring George Clooney. The perceptual gap between the two is both cultural and generational and reflective of the difference between the Soviet space program’s metaphysical probings and the American focus on scientific data — or as one might say, the mythic versus the technological.

This brings us to a comparative study – that of Yuval Sharon’s new production of Meredith Monk’s exploratory three hour long opera ATLAS, originally staged at the Houston Opera House in 1991. To be clear at the beginning, this was not a collaborative enterprise, but one in which Monk gave her consent as an “experiment” to see if it was possible for someone else (with extensive resources) to stage a work in need of revival. No doubt Sharon came to this project with the best of intentions and great admiration for Monk’s work. However his version ended up less of a reconstruction and more of a personal interpretation in which spectacle and technology replaced the meditative and mythic qualities central to Monk’s work and sensibility. While Sharon remained true to Monk’s orchestral musical composition, and to a good degree to her unique vocal techniques, the visualization was a far cry from Monk’s very particular minimalist visual concepts and aesthetics that are not matters of style but of philosophical substance. Monk has stated that “Musical, gestural and visual motifs recur throughout (the opera), functioning as perceptual codes, delineation of character and situation, and expression of the passage of time…. In addition, codified visual motifs provide a subliminal layer of content.” Despite his passion for her music, Sharon’s penchant for “cool” techno gimmicks as a popular attraction for “operatic” scale works was a misfit to Monk’s understated mise en scene and timeless evocations of place.

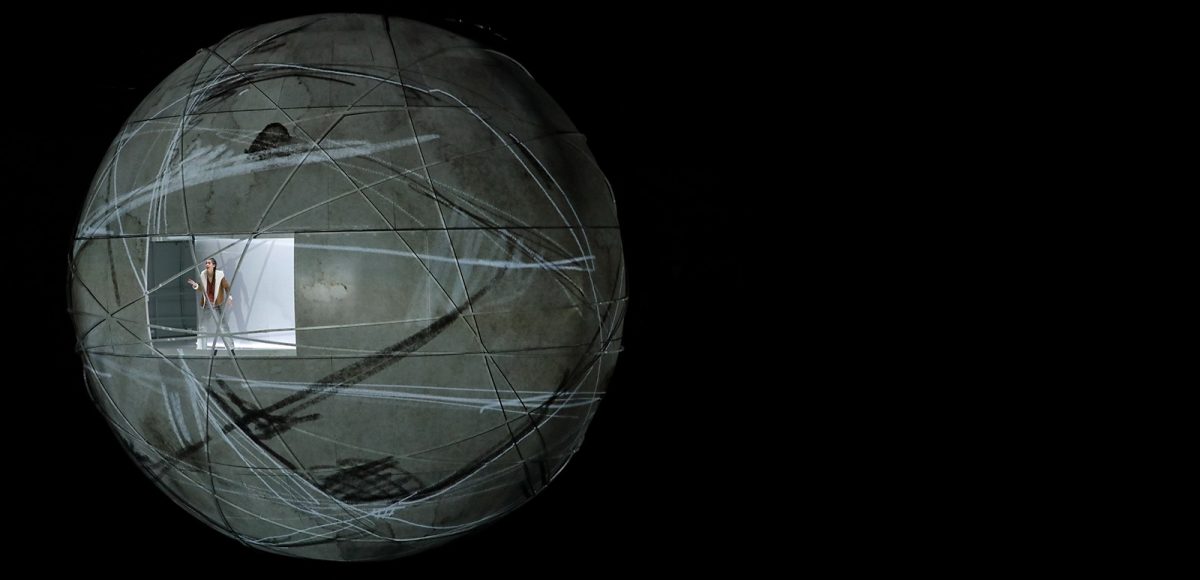

In Sharon’s production an enormous globe covered with moving projections was suspended in the air, visually dominating the Disney Hall space. It loomed over the performers beneath it, reducing them to doll-sized miniatures, shifting the focus from the human condition to that of the dominant “smart” object. Its presence was dualistic: at once obdurate in mass and scale, and illusory when its surface was covered with text messages and images, making it a metaphoric communications satellite. Then again, when at one point it opened to reveal performers in an alcove inside it, the effect was more that of an orbiting spaceship than a planet. Contrary to the science fiction implications of this technological spectacle, Monk’s narrative is very much earth-bound, mapping not only the terrain traveled across, but also the internal landscape of consciousness where the spirit both resides and transcends its physical and temporal limits.

Monk’s ATLAS is a woman’s odyssey in search of knowledge, not only of other cultures but of self, through the directness of immersed experience. It is a quest for a transcendent understanding, a unifying ecology of nature, culture and spiritual harmony, propelled by the desire to find one’s inner vision. The story is very loosely based on the travels and life of Alexandra David-Neel, an explorer, writer and Buddhist known for her journey to Lhasa, Tibet in 1924 when it was still forbidden to foreigners. In ATLAS Alexandra Daniels and her traveling companions traverse four symbolic places – the fertile prairie, the frozen Artic, the dense Forest, and the vast Desert all of which are essential parts of the Earth’s now endangered ecosystem. Dwelling in each of these places are its inhabitants along with imaginary spirits and demons, all with lessons to be imparted, tested and learned. Along the way each of Alexandra’s four companions undergoes an ordeal that tests his or her inner resources. Over three hours the opera spans half a century from Alexandra’s adolescent dreams of far away places to her encounter with her Spirit Guides and her departure on her adventures; from her interviews of traveling companions, through her global explorations, challenges and spiritual quests, to her return home having found inner wisdom.

MEREDITH MONK, ATLAS 1991. AGRICULTURAL SCENE. PHOTOS: JIM CALDWELL

While Sharon’s remapping retained the basic storyline, the places where it went astray were in its visualizations and characterizations. In all her works Monk’s approach is mythic, neither historical nor contemporary, and her staging is grounded in ritual and a poetic synthesis of sound and gesture inseparable from each other. It is as if the vocalizations generated the gestures from the inside out and vice versa. In the words of critic Bonnie Marranca “Texture of voice is more important than text in this opera that dances. The musical line, which overrides any sense of literary line, is inseparable from the line of the body.” And here is where Sharon’s 2019 version of ATLAS went badly off course by not understanding that essential relationship. Instead of meticulously adhering to Monk’s choreography, it was inexplicably replaced by a lot of expressionistic gestural excess, with dancers flailing about in a manner reminiscent of modern dance of the Martha Graham school. This is antithetical to Monk’s precise synchronic movement vocabulary. The result was that every action was overplayed or overstated, as if Sharon as a director did not trust his audience to be able to comprehend Monk’s level of abstraction.

To make matters worse the costumes were equally out of tune in their attempt to be “contemporary” whether overly casual millennial garb, overdone “fashion”, or “futuristic” fantasy. Monk’s costumes on the other hand are a form of symbolic “signage” deeply integrated with her content. Drawing upon a variety of world cultures across time, they are at once timeless and universal. The result was that Alexandra and her companions came across more as cultural tourists in their encounters, outsiders rather than visitors who humbly and joyfully joined in with their host community’s rituals and customs.

To return to the huge orb, when a section slid open to reveal the performers in a shallow alcove at the Equator level, only one portion of the audience was privy to seeing the action inside, while the rest of us only had frustrating partial views. It was in this claustrophobic chamber that Sharon chose to stage the scenes where Alexandra interviews her prospective traveling mates, thereby confining the action rather than allowing space for the scene to impart the expansive wide open nature of what they were about to embark on. In addition it cramped the comedic aspect of the performers vocals, postures and gestures. Likewise the following airport scene was more a statement on the crowded uncomfortable nature of contemporary air travel, than the anticipation and uncertainties of the unknown adventure that awaits our explorers.

ATLAS 2019 PHOTO: MATHEW IMAGING

This is not to say that the idea of a floating orb could not have worked had it been an extension of Monk’s own sensibility. It might have functioned simply as a projection screen topographically mapping our fragile planet and expanding the mise en scene of each visitation with images of those iconic landscapes now so environmentally endangered. Finally it could have been a little smaller so as not to so overshadow the performers below, and perhaps tilted at 23 degrees like the Earth.

Sharon refers to Stanley Kubrick’s sci-fi classic 2001 as a source of inspiration. Perhaps he should have looked at Tarkovsky’s Solaris instead. He seemed not to have fully grasped the way Buddhist dharma has informed Monk’s work and how it was infused into Alexandra and company. For he would have recognized that the demons and spirits live within us not as separate entities in the outside world, and the struggle towards self-knowledge and enlightenment is an internal one. Transcendence doesn’t take place in outer space, or another realm but in the dimension of consciousness. Having positioned his previous operatic spectacles within the domain of arty entertainment has brought Sharon much recognition, accolades, and resources. But subtlety and nuance are not part of his oeuvre.

Flaws aside, Sharon is to be applauded for his dedication to the music. He clearly put much effort into both the L.A. Philharmonic’s performance of Monk’s composition as written, and the singers’ vocal renditions. They were required to learn Monk’s unique techniques and the challenge was well met. There were several outstanding vocalists, and the music was gorgeous and uplifting. The difference is that the members of Monk’s own ensemble whom have been with her for many years have internalized the music so that it comes through the body from the inside out, rather than learned and externally “performed.” For the newly acquainted audience member this was not apparent and the experience of the music was undoubtedly exhilarating. Just as for those unfamiliar with Monk’s oeuvre, this staging of ATLAS may have been a satisfying theatrical evening. But that is not the issue.

I need not go through all the subsequent scenes to show how the problems of interpretation manifested themselves. The point has been made. Rather I return to the initial issue of how an auteur multidisciplinary artist and performer like Monk can preserve the authenticity and meaning of her work beyond her own lifetime. One lesson learned in this particular instance is that it doesn’t work when another ambitious auteur of a very different generational sensibility and priorities simply uses the music as the foundation for his own version. Not so different than when a filmmaker adapts a brilliant novel, using the basic plotline and characters but losing the literary richness of the language that provides the substance and deeper meaning. Making a Don DeLillo novel into a film is bound to fall short if not totally fail.

There is of course a way to revive and restage an auteur work such as Monk’s. That is to go back to the original as much as possible. The perfect example of that is choreographer Robert Joffrey, dance historian Millicent Hodson, and art historian Kenneth Archer’s brilliant reconstruction of Vaslav Nijinsky’s 1913 Le Sacre du Printemps.” Through painstaking research and with the aid of Marie Lambert who was Nijinsky’s assistant in 1913, they restored not only his choreography as set note by note to Igor Stravinsky’s music, but the costumes conceived as part of it, as well as the stage sets. Far ahead of and in many ways beyond its time, more than a century later Le Sacre remains as powerful and relevant a work as ever, and surprisingly contemporary.

Monk and others like her can prepare full documentation — staging instructions, scripts, musical, vocal and choreographic scores, costume design, set concepts, etc while they are still active creative artists, and arrange for this material to be responsibly archived and housed. And perhaps in fifty years if there is still a habitable planet someone like the late Robert Joffrey will reconstruct Monk’s original work for a new generation and reveal how prophetic and timeless it is. In the meantime let’s hope that Monk, now in her mid-70s finds the will and means to remount her 1976 opera Quarry, a work about fascism that is more profound and illuminating now than ever. Fortunately a newly restored, long-awaited film of this work is now available. What Monk and artists like her need today is not a young impresario director, but a producer who will raise the funds and venues, and stay clear of the artistic vision.

Cover photo: Mathew Imaging

ATLAS

Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles

June 11, 12, 14, 2019

Yuval Sharon, Director

Es Devlin, Designer

L.A. Philharmonic New Music Group

Paolo Bortolameolli, Conductor

Meredith Monk, composer