UCLA Hammer Museum

Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933-1957

Through May 15, 2016

What becomes a legend most? An exhibition that traces its life, its dynamics, and its impact on subsequent human thought and activity. The modern history not just of art pedagogy, but art itself, was shaped largely by a few art schools – schools, not incidentally, noted for more than just education and indoctrination. Black Mountain College is one such school, a center for exposure to and training in new ideas and forms in all the arts that arose at a crucial moment, shaping American artistic practice when that practice was ripest for shaping. Leap Before You Look excavates Black Mountain College, looking less at what impact it had on American postwar art (a well-worn subject) and more at why it had such an impact and what made it tick when it was ticking.

Leap Before You Look unpacks the Black Mountain experience, laying out the history of the college (which was anything but a school exclusively for the arts) and then examining every facet of its instructional offerings – and, more to the point, every significant instructor, pupil, and visitor. Necessarily, the survey regards individual creative personality as the crucial element in the Black Mountain dynamic; the school’s artistic curricula, after all, were shaped not by a unified foundation-to-specialization program, as at the Bauhaus, but by the sensibilities of the people conducting classes, and hardly less by their students.

It should be noted that the Black Mountain College we remember as an artistic hotbed was so mostly during the summers. This befitted both the live-work ethos of its community (who tended gardens, built structures for the school, etc.) and the experimental ethos of its artists. Master teachers such as Josef Albers taught year-round, but invited many colleagues – who often promulgated very different styles – to teach as well during the special summer institutes held in the late 1940s and early ‘50s. Such a conflation of art institute and summer camp had profound results.

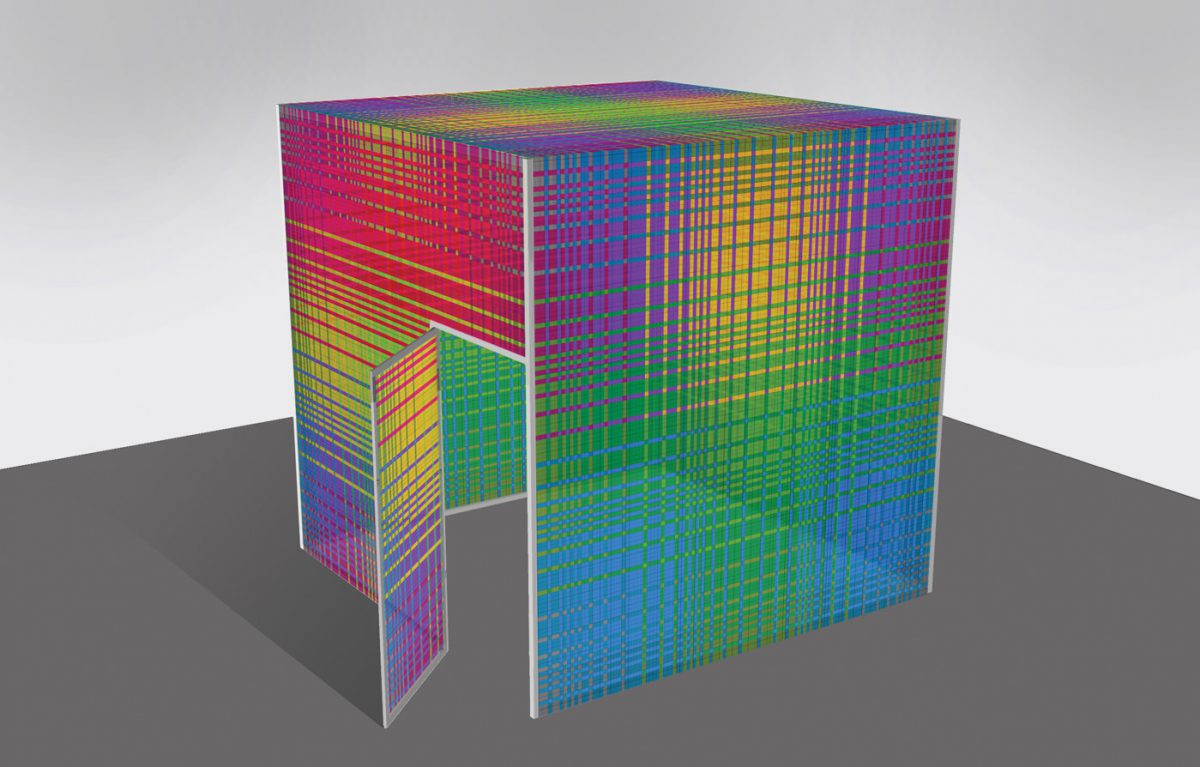

Look Before You Leap doesn’t simply introduce us to these results, it illustrates and explains them with a satisfying thoroughness – and a nimbleness and equanimity appropriate to the subject. It gives equal weight to Albers’s pedagogy and to that of his wife Anni, who taught textile design and production. It finds continuity among painters as disparate as abstract expressionists Willem and Elaine de Kooning and constructivist Ilya Bolotowsky. It cleverly superimposes pottery and poetry, not (just) for the sake of the near-homonym but also for history’s sake (as these two art forms endured especially late into Black Mountain’s waning years). It unearths now-obscure teachers and students and places them, to no disadvantage, with their better known peers. And it captures the ambience of the community and the spirit of its members through extensive photo-documentation produced by devoted shutterbugs like Hazel Larson Archer. Now-revered figures such as Buckminster Fuller, Ruth Asawa, and Robert Rauschenberg certainly get pride of place in the show, but that’s understandable: their work and attitudes had a notable impact on the Black Mountain experience not just in hindsight, but at the time.

It isn’t easy to design and mount a show that must frequently jump scale and medium to encompass the variety of its many subjects’ styles. Leap Before You Look does so with as much grace as clarity. Taking advantage of the Hammer’s own flowing layout, the show (which did not originate here) posits discrete displays of particular people and disciplines that abut one another with the doubled logic of formal connection and chronological sequence. The show comes to a crescendo of sorts in the rooms devoted to music and dance, for it’s there that the John Cage-Merce Cunningham-Rauschenberg team is forged and goes on to re-invent the world. However spectacular, though, it’s a thoughtful crescendo. There is, alas, precious little documentation of Cage’s multivalent multi-media 1952 Theater Piece and none of productions such as the 1948 staging of Erik Satie’s Ruse of Medusa, starring Fuller, Cunningham, and Elaine de Kooning. (The massive catalogue, of course, provides such documentation.) But the immense screen showing early performances of even earlier Cunningham choreographies makes up for these lacunae.