THE LANDING, LOS ANGELES

Rat Bastard Protective Association

(October 1, 2016-January 7, 2017)

SAN FRANCISCO MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

Bruce Conner: It’s All True

(October 29, 2016-January 22, 2017)

KOHN GALLERY, LOS ANGELES

A Movie: Bruce Conner

(November 12, 2016-January 14, 2017)

MARC SELWYN FINE ART, BEVERLY HILLS

Jay DeFeo: Paintings on Paper, 1986-1987

(November 5, 2016-January 7, 2017)

Its New York and Los Angeles scenes notwithstanding, the late-1950s/early-60s Beat movement was based in San Francisco. It had a literary home at City Lights Books in North Beach and an artistic one at “Painterland,” the multi-studio complex in the Fillmore District. It was at Painterland that Bruce Conner established the Rat Bastard Protective Association. Under this playful moniker gathered most of the artists working in the complex, and a broad swath of their friends besides. In fact, by time the Association formed, painting wasn’t the only, or even the dominant, practice in Painterland. Conner and others in his cohort were rapidly moving from painting to assemblage, excited by the expressive potential “found objects” afforded.

As the stunning exhibition – worthy of a small museum – at Landing demonstrated, some Rat Bastard artists went wholly over into pasted papers and cobbled-together objects, while others kept painting but took a more and more extravagant attitude toward putting pigment on support, often combining scraps and discards into their paints to give their textures – and, more importantly, their imagery – an abject quality. The Landing exhibition also showed how important drawing remained, even to the most devoted assemblage aficionados: something about paper, as surface and as stuff, provoked the Rat Bastard Protectivists into productive paroxysm. Perhaps their friendships with Beat poets such as Michael McClure gave them a jones for the page itself. Perhaps their sensitivity to the news of the times made them see their own art as a kind of newspaper of the soul. To be sure, the Landing show featured great painting and sculpture by Carlos Villa, Wally Hedrick, Joan Brown, Robert Branaman, Manuel Neri and the under-remembered Alvin Light. But it’s the drawing and the assembling, realized by the likes of Jean Conner (Bruce’s wife), Wallace Berman, and George Herms, as well as several of the painters and sculptors, that gave the show its meaning and character.

Painterland was a magnet for very gifted people, but Bruce Conner was the genius at its heart. His vision was so broad, ambitious and complex, and his world view so incisive and ornery, that out of necessity he became, as was said of Picasso, “pathologically inventive.” “Bruce Conner: It’s All True” clarifies Conner’s voluble, mischievous, anxious, angry, verbal, visual and musical sensibility, almost to the point of confusion. But it’s a giddy, enlightening confusion, an adventure not simply into someone’s head but into worlds of experience, whether it’s the Cold War, the Punk Scene or psychedelia. Assemblage was perfect for Conner, a way of breaking down and rebuilding the world; but after he gave up the practice in the mid-60s (deeming it too popular), he maintained the bricoleur attitude and sense of adventure, coming up with maze-like drawings, photogravure collages, ink-blot washes, body-sized photograms, rock-and-roll photography and myriad other devices and gambits. For instance, the survey includes documents from Conner’s 1967 run for San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors.

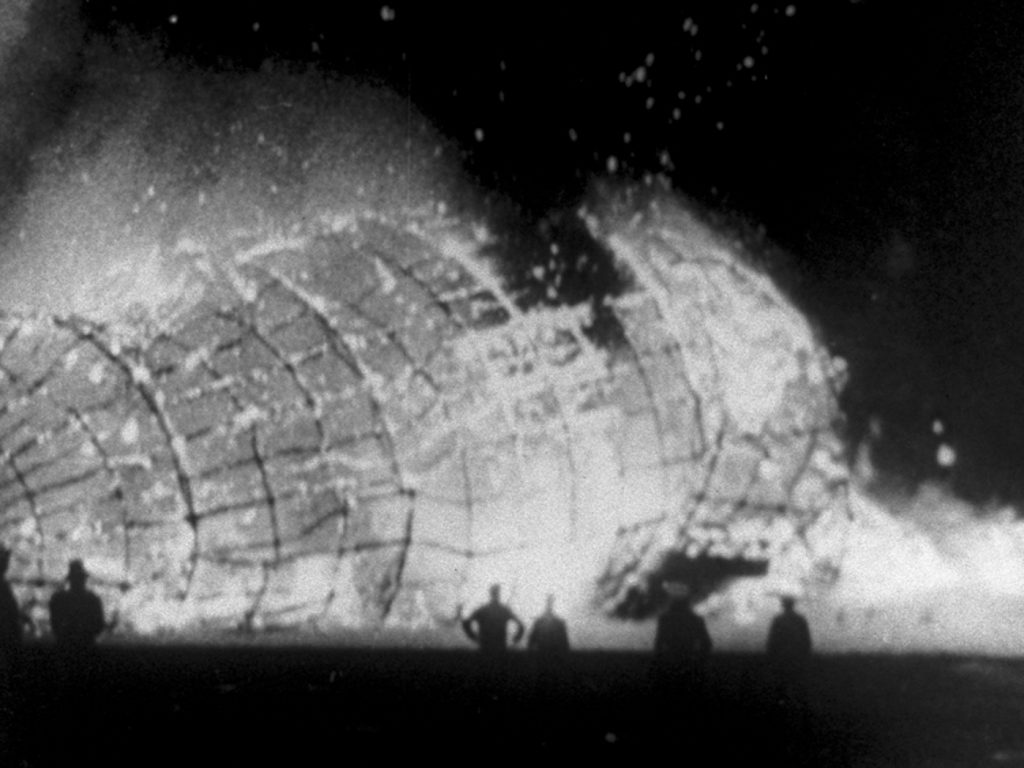

Meanwhile, in LA, Kohn Gallery currently devotes itself (until mid-January) to a single work of Conner’s, “A Movie.” Conner was one of America’s great underground filmmakers, more or less inventing the found-footage film with this 12-minute 1958 masterpiece. It’s one of three films shown at critical junctures in the museum retrospective, but here the gallery’s main room has been converted into an austere movie theater in which “A Movie” shows continually (as originally intended). Conner’s hyper-montaged imagery jumps from bathos to pathos in the blink of a jump cut, but themes of destruction and elation quickly emerge, choreographed and moved along by the Pines of Rome soundtrack. (Respighi’s tone poem, Conner sensed, was movie music avant la lettre.) It’s one of the most ecstatic and profound artworks in any medium to come out of the Beat era.

Conner’s friend and fellow Painterlandian Jay DeFeo is best known for her painting The Rose, which took her the better part of a decade to make and weighs nearly a ton (and whose removal from her studio is the subject of another Conner film). But she was a brilliant painter – and photographer and collagist – for her entire career. Her paintings on paper shown at Marc Selwyn were produced after an extended trip to Japan, two years before her untimely death at 60, and show DeFeo at the top of her game. The modestly sized, gray-scale paintings – actually rendered in a variety of media – have at once a gravitas and a muscularity to them, and seem sometimes to portray a struggling force, while at others, a force at contemplative rest. Lighter areas glow as pockets within darker. Fittingly, DeFeo called these her Samurai series, as they have the centered energy of the fabled Japanese warriors.

As the “Rat Bastard” roster reflects, DeFeo was one of a number of women prominent in the postwar Bay Area scene and now recognized as of the same level of importance as their male peers. Deborah Remington was not a Painterland person, but her commitment to gestural painting and, especially, to the mysteries of imagery equaled those of her Beat friends – and, if anything, came to surpass them. There are a lot of sketches and studies for Remington’s work from all periods in this traveling mini-survey, and it is fascinating to see her early abstract expressionist vocabulary crystallize into a strange, glowing kind of organic geometricism the likes of which have not occurred otherwise in modern art. Several large works on paper from the 1960s and 70s – which anchored the Los Angeles display – approximate the impact of the paintings, but almost everything in the selection, even many of the early ab-ex works, has that glistening, inexplicable allure. If Bruce Conner was a genius because he couldn’t stop investigating and inventing, Deborah Remington was one because she had to make images no one else could have imagined, much less made.