He calls himself a compulsive image-maker, drawn to the urban environment, the accidental geometry of the city, the intersecting curves and planes of the modern world and the interplay of light and shadow in the human environment. An Englishman now based in Tucson, Arizona, Andy Burgess gained recognition as a painter of urban landscapes—the same subject that also suits his photography. He has had a ‘serious engagement’, as he calls it, with photography and its processes for more than 25 years, recently culminating in the series Narratives, (mainly shot in the last year or two in Tucson, Denver and Southern California). In this latest body of work, Burgess explores an interest in the city as a vibrant place of culture and creativity and a repository for dreams and ambitions. Burgess’ form of street photography features a quiet aesthetic influenced by abstract art and modernist preoccupations.

“My interest is in classic photography,” Burgess explained. “I enjoy analog, working with a prime lens, black and white film and printing in the darkroom on silver gelatin, like for this series. Back to the roots.”

During the past few years, Burgess has been increasingly drawn back to analog forms of expression as an antidote to the ever-more-dominant digital and mediated online experience. “Perhaps it’s a reminiscence from my past as a painter, wanting everything to be handmade and to have a physical presence. I want to stay clear of making art in a digital way.”

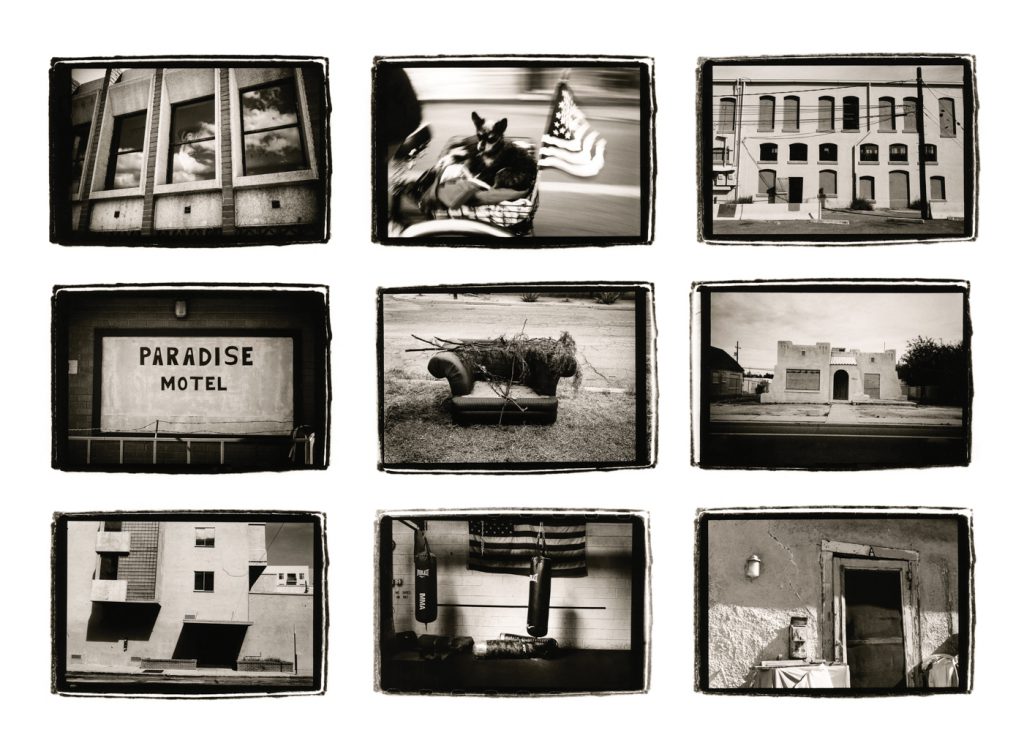

Besides what the picture shows, the print itself has inherent value for Burgess as art. The same goes for the practice of showing his Narratives series in ‘groupings’ of images: grids of nine that add a narrative dimension to the work. He refers to it as, “A beatnik journey into the American psyche and a poetry of light and shadow.”

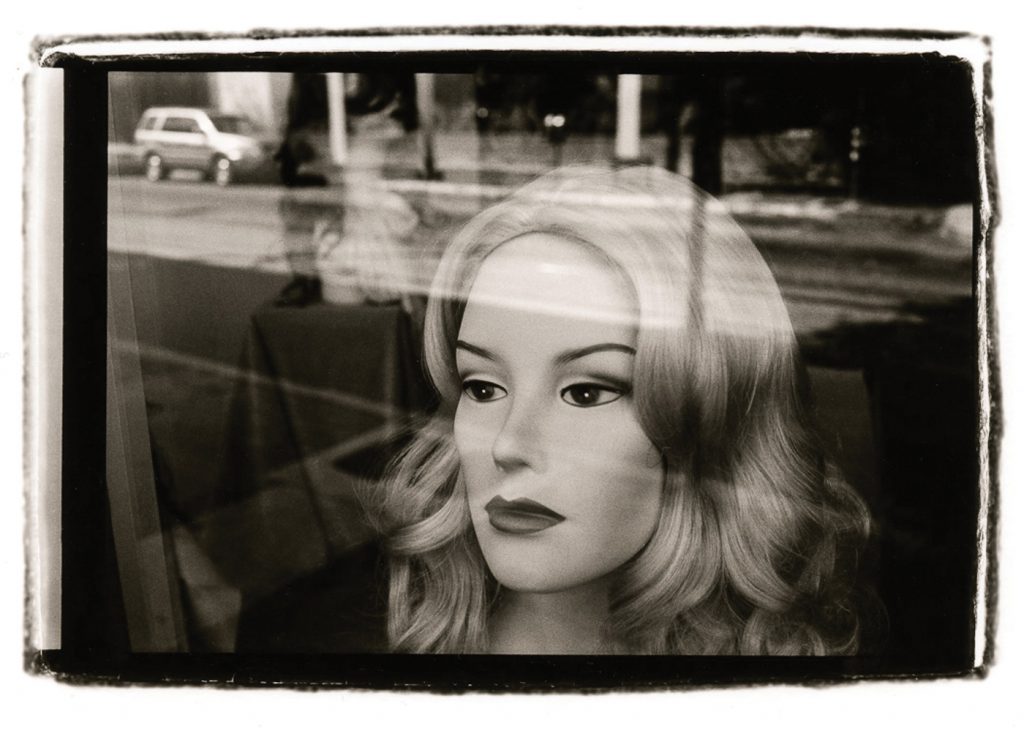

Burgess acknowledges that his images by themselves are quiet and humble, not focused on major events or dramatic landscapes. Therefore, the images from his latest series are not groundbreaking, but the cinematic narrative that emerges from putting them together tells a story about feelings. and about light. Burgess likes to describe it as “looking at the overlooked,” just as the renowned art critic Norman Bryson famously described still life painting. “I try to avoid the more obvious subjects and seek poetry in the mundane, the ordinary and the discarded. I’m fascinated by the remnants of the past found in the peeling paint and street signs of our downtowns, the melancholy of the broken and abandoned.” It’s what Burgess’ eye — and at the same time, psyche — is drawn to when stepping outside to photograph. Looking for the beauty of imperfections, he feels connected to the aged, the discarded, the beaten and the ugly. “All objects possess personalities and histories that imbue them with spiritual value,” Burgess said.

Burgess’ photography is a study in the melancholic, snapping lost moments because they’re gone the moment you’re done. “Taking a black and white photograph of a hand painted sign that’s dilapidated is a throwback, a double signification of things that have passed.” It’s no wonder that presence and absence are other recurring themes in his work. Burgess always appears to be looking for the soul in objects and surfaces that rarely reveal their full meaning.

When darkroom queen Terese Engle came across his work, she was duly impressed. Engle has printed some of the great photographers of the 20th Century, including Robert and Cornell Capa, Lucien Clergue, Dorothy Norman and Bruce Davidson. A chance meeting between Engles and Burgess has resulted in a collaboration —to be shown at Photo Independent in Los Angeles—combining Engle’s lofty printing aesthetic with Burgess’ distinctive visual preoccupations and camera eye.