Refuse The Hour

Refuse the Hour takes place inside the constructed world of William Kentridge from the projected environs of his studio to the theatrical set inhabited by his eccentric time-measuring mechanisms, dancers, and musicians. It is the manifestation of the artist’s creative process as he investigates the measurement and manipulation of time, the problem of human perception, and the question of control — mere chance or fate.

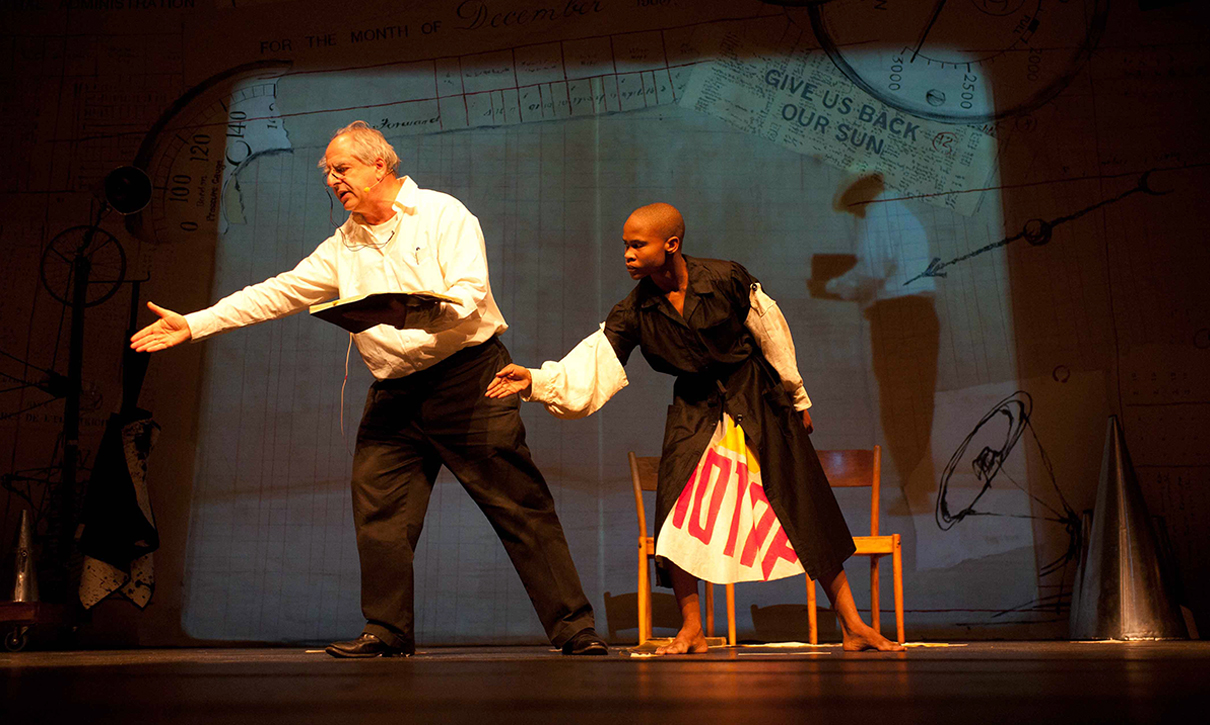

Photo By John Hodgkiss

At the center of all the action is Kentridge himself, a visual artist of remarkable range, diversity and intellect, and an equally skilled and charismatic performer. He is the mastermind inventor and storyteller who delivers a series of historical anecdotes and philosophical musings, laced with mythological, scientific, and poetic references. Dressed in black pants and white shirt, white-haired and soft-spoken, his voice and manner brought to mind Anthony Hopkins as Robert Ford in Westworld. He is just as mesmerizing and the questions he raises are equally compelling.

It begins with the problem of Perseus who, despite an epic journey through great dangers and obstacles which by all logic should have altered his course, ends up fulfilling the prophesy of killing his father anyway, not by intent but by accident. Could he have escaped his fate? Alter the course of time that led to an otherwise unlikely conclusion? Can any of us? Are we bound by destiny or merely coincidence in an unpredictable universe? It reminds me of the possible parallel paths in the film Run Lola Run in which the circumstances generating the ten seconds differential of when Lola arrives at the curb determines whether or not she will be struck by a car. Is that an accident, mere luck, or some mysterious order in the algorithms of time? Do we all inhabit multiple timelines in which we live in one, and die in the other? In her novel Life After Life Kate Atkinson replays this scenario over and over. But Kentridge plays out the dilemma of Einstein’s theories of spacetime by demonstrating how our perceptions of time shape our experience as the clock ticks.

In past time on film Kentridge paces his studio, his mind a kaleidescope of thoughts, ideas, questions, calculations, all colliding into each other and spinning around. He changes the speed of his walking as he marks, counts and measures. On stage every thought is put in the context of history, simultaneously activated verbally, sonically, visually, and kinetically. Kentridge’s discourse explores the problem of speed and measurement, light versus sound, mechanized synchronization versus the human body in motion, an expanding universe versus entropy and black holes. Then there is the matter of the invention of photography and its ability to “stop” time, Muybridge’s studies of bodies in motion, cinema in which time can move forward and backward, and riffs on clocks and trains and Greenwich time. He even cites Einstein’s twin astronaut paradox. The juxtaposition of time past and present, and the interaction of his two selves in recorded and live time further illustrates his attempt to understand the malleability of time and the futility of trying to control it.

Photo: John Hodgkiss

Kentridge’s time-traveling narration is materialized by outsized silver megaphones through which performers shout tempo directions at three giant metronomes made from found materials like a Kurt Schwitters assemblage, as they mark time at different speeds and directions at different times. Interacting with the set are singers, dancers, musicians, and wall-sized video projections. There is also a tripod and a bicycle wheel, a sly reference to Marcel Duchamp. An extraodinary dancer Dada Masilo’s costume mirrored her name, her skirt echoing a Tristan Tzara typographic collage in motion as she spun through space like an orbiting energy particle, interacting directly with Kentridge. At one point she became an animated Cubo-Dadaist object resembling Hugo Ball with megaphones on arms and a leg. At another point a dancing double made of newspaper fragments like a cubist collage was projected behind Masilo, aptly noting the simultaneous arrival of Einstein’s equation and cubism’s visualization of the 4th dimension.

Photos: John Hodgkiss / Phinn Sriployrung

Music, one significant way of marking time, plays a key role throughout, starting with the chaotic poundings of a mechanical drum set. Composer Philip Miller’s raucous score is a wildly eclectic mix of musical sources and overlapping styles. Performed live by a rousing brass band, percussion, keyboards, and a strangely altered violin, it combines jazzy early 20th century dance music, an oom-pah tuba and African rhythms, with modernist dissonance and sound effects, plus some gorgeous vocals from South African opera singer Ann Masina. An imposing physical presence, in one scene she looms above us as she sings a haunting rendition of Berlioz’s Le Spectre de la Rose, while Joanna Dudley, looking as if she stepped out of Cabaret, counterpointed Masina’s aria by singing phonemes and pitches backwards like in a Futurist sound poem. The juxtaposition of this dynamic ensemble of South African musician/performers in Greta Goiris’s extravagantly colorful African costumes with early 20th century avant-garde visual art and cinema also suggested an underlying temporal and political narrative about European colonialism in Africa.

Photo: John Hodgkiss

Photos: Phinn Sriployrung

At the heart of Refuse the Hour is the matter of mortality itself. No matter what we do we cannot stop the progression of all living things from birth to death, each in its own time. Yet despite the fact that we mark time in a linear progression of minutes and hours, days, months and years, it is actually mutable, circular, relative. Thus Kentridge refutes death with a comforting notion of immortality — that being that everything lives on in time and space. The universe is the repository of everything that has ever existed and happened carried across the galaxies by particles and waves of light and sound. The things that happened centuries ago are still alive in the telescope of a planet hundreds of light years from here.

In many ways Refuse The Hour is the prequel to Robert Wilson’s 1977 ground-breaking, five hour opera Einstein On The Beach that begins where Refuse The Hours leaves off. For whatever reason Kentridge decided to stop in the 1920s at the point when we begin to believe in the supremacy of technology over nature. He leaves the 21st century dilemma of digital time consuming, digesting, and annihilating biological time open to future speculation. In the meantime in Refuse the Hour, Kentridge and his conceptual collaborator Peter Galison leave us with much to contemplate about the nature and meaning of our constructed reality and our existence within and beyond it. And isn’t that what art is supposed to do.

Tesseract

There is no narration or historical timeline, in Charles Atlas, Rashaun Mitchell and Silas Riener’s Tesseract, a multimedia production in two autonomous parts- a film and a live performance. Instead time is explored in the first part through the visualization of mathematical descriptions of the fourth dimension traversed by seven stunning dancers. There is no linear progression in the film’s dream-like journey through revolving and evolving spaces. Instead Tesseract is a kinetic visual time/space odyssey in which the performers, not unlike David Bowie in The Man Who Fell To Earth, seem either like visitors to alien worlds or alien beings on our world, depending on your perspective.

The connecting thread throughout is a tesseract, a four-dimensional analog of a cube that can be seen in animation whenever it shows a smaller inner cube inside a larger outer cube. The hypersurface consists of eight cubical cells. The eight lines connecting the vertices of the two cubes represent a single direction in the “unseen” fourth dimension – time. Hermann Minkowski’s 1908 calculations that consolidated time into spacetime became the basis for Einstein’s theories of Special and General Relativity. This is the realm in which Tesseract takes place.

Photo: Nathan Kay

The forty-five minute film in six segments viewed with 3-D glasses, begins with an animated tesseract, which appears and disappears, draws and redraws itself, morphing from a linearly defined moving object into an architectural construct, to a conceptual space. Like visitors in a series of strange yet oddly familiar virtual landscapes, the dancers traverse each new environment, as one space dissolves into another. They test the limits of their bodies in space, and the forces of gravity, sometimes in form-altering costumes that interact with the landscape. In one segment the dancers occupy diagrammatic geometric structures floating like space capsules over a rocky orange desert landscape, growth-like protrusions extending from their orange bodysuits. In others their sinuous silver forms navigate a white foggy weightless airspace, or swim like sea dwellers never seeming to touch the ground, or fall to the ground at high velocity in a black and white interior, bodies rolling with a thunderous sound. At the end it all folds back into a tesseract in outer space, tiny points of light flickering like distant stars. The film is a sci-fi magical mystery tour that evokes the potentialities of how life forms might adapt to their environments be they organic or synthetic. The possibilities are as boundless as the biodiversity of this planet, most of which we never see, or notice, and are now seriously endangered.

If the film exists in kaleidescopic mutable time, the live performance visualizes synchronistic parallel time as if the multiple dimensions all around us were visible. This is achieved by the interaction of live video with the live performance allowing us to simultaneously see the dancers past, present and future from multiple viewpoints.—front, side, and back. The cameraperson is onstage with them and Atlas manipulates the images as they are projected in such a way as to shadow, dislocate, and relocate them in time either instantaneously or in a matter of seconds. The effect is ghostlike, as if you could witness your spirit rising out of your body at the moment of death. Or from another perspective, if you could actually see the images of where you have been and where you are going as a projected light form. These “spirit-bodies” loom, float, levitate, and dance above and around the live bodies, changing scale, speed and location. They are weightless, matter transformed into energy, unbound by gravity as they are set aloft in space and time.

Photos: Ray Felix/EMPAC

And then there is the dancing itself. The choreography by Mitchell and Riener, both accomplished Merce Cunningham dancers, fully utilizes Cunningham’s movement vocabulary and philosophy while extending it into new terrain. The dancing is exhilarating. The energized body moving in and through space testing the limits, unembellished by narrative or emotional content is Cunningham’s timeless legacy, and the dancers, including Mitchell and Riener, carry it forward with clarity, precision and eloquence. Add the interplay with the projected images and it becomes transporting and utterly contemporary. For in this digital age we leave traces of ourselves everywhere, intended or not. Our images, thoughts, tastes, habits, likes and dislikes make up virtual ghost portraits that exist beyond our awareness. They shadow us in the ether.

Photos: clockwise – Ray Felix/EMPAC, Nathan Kay, Ray Felix/EMPAC

In the second act of Tesseract Atlas employs technology to reveal the mysteries of our corporeal existence, making it the kind of kinetic visual work that needs to be experienced in real time and space to fully appreciate its deeper levels of meaning. But perhaps like Kentridge’s idea of immortality, Atlas’s ghostly time-traveling projections and the dancers that generated them will live on not only in our memories and imagination, but to be retrieved in the future at another point in spacetime in this expanding universe or another. There is something uplifting, maybe even transcendent in that idea, that ought to inspire us to do better in the life we are living.

Photo: Nathan Kay

Refuse the Hour / William Kentridge

Philip Miller (Music) Peter Galison (Dramaturgy) Dada Masilo (Choreography) Catherine Mayburgh (Video design)

Adam Howard ( conductor, trumpet and flugel horn), Tlale Makhene (percussion), Waldo Alexander (violin)

Dan Selsick (trombone), Vincenzo Pasquariello (piano), Thobeka Thukane (tuba), Thato Motlhaolwa (actor), Dada Masilo (dancer), Ann Masina (vocalist), Joanna Dudley (performer/vocalist)

UCLA Center for the Art of Performance

Royce Hall, November 17-18, 2017

Tesseract / Charles Atlas, Rashaun Mitchell, Silas Riener

Dancers: David Rafael Botana, Kristen Foote, Eleanor Hullihan, Kate Jewett, Hiroki Ichinose, Cori Kresge, Rashaun Mitchell, Silas Riener, Melissa Toogood.

REDCAT (Roy and Edna Disney/Cal Arts Theater), downtown Los Angeles.

November 30 –December 3, 2017