Henri van Noordenburg’s studiously enriched photographs of landscapes reflect his Dutch heritage in several ways. Most obviously, they began life as archival images of 1940s farm houses and environs once situated near the city of Amersfoort, about 50 kilometers south-east of Amsterdam, where his father’s side of the family came from and where van Noordenburg rode his bicycle every morning on the way to school, often with wind and rain in his face. It’s easy enough — confirmed by van Noordenburg — to also make a modest historical link to the prints and drawings of northern European masters such as Pieter Bruegel or Albrecht Dürer.

‘I love the look of the thick clouds so often depicted in Bruegel’s work,’ he says, ‘clouds that promised the dreary rain.’¹ These clouds appear in an earlier series of compositions titled ‘Efface’ in which the artist appears nude, a mostly small but vital figure haunting or haunted by the brooding scapes of thick bush under billowing grey and white skies. The series, begun in 2010, was the first time van Noordenburg printed an image — himself in this case, in full color — on large-format paper with a black background. Through a delicate process of engraving or etching the featureless dark areas using a scalpel, van Noordenburg reveals the lands and cloudscapes that the figures inhabit. While the images translate as landscapes, he notes that ‘the essence is about what is added, altered, or removed.’

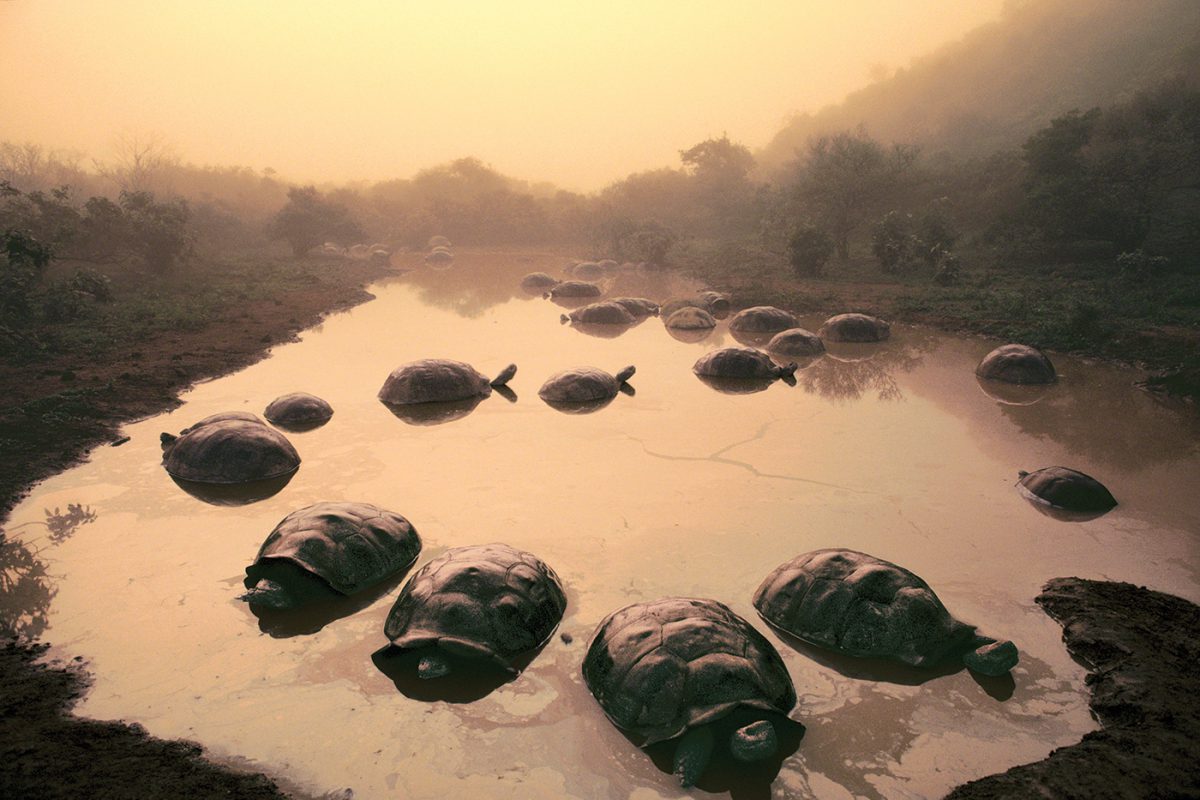

In his recent series of monochrome-blue landscapes called ‘water line’, van Noordenburg uses a similar lengthy process of transferral and printing on large-format paper followed by the fine-tuned scraping and engraving technique. The images impart more than the 1940s originals did, emerging as revelations of his imagination. The old farm photos now draw on, as the artist says, ‘what I imagined the landscape to look like and my memory of it as I saw it years later.’ We see them with an invented life: intricate and overhanging trees have been added, outer-buildings and fences appear, along with flooded land and subtle reflections. Van Noordenburg presents an intriguing personal narrative of fact and fiction, European and melancholy but lyrical as well, maybe even universal.

9-Zevenhuizerstraat-E-561

9-Zevenhuizerstraat-E-561 ZEVENHUIZERSTRAAT © HENRI VAN NOORDENBURG

ZEVENHUIZERSTRAAT © HENRI VAN NOORDENBURG OORLOGSGEWELD © HENRI VAN NOORDENBURG

OORLOGSGEWELD © HENRI VAN NOORDENBURG OORLOGSGEWELD © HENRI VAN NOORDENBURG

OORLOGSGEWELD © HENRI VAN NOORDENBURG LIENDERTSEWEG © HENRI VAN NOORDENBURG

LIENDERTSEWEG © HENRI VAN NOORDENBURG VOORDERSTEEG © HENRI VAN NOORDENBURG

VOORDERSTEEG © HENRI VAN NOORDENBURG LIENDERTSEWEG © HENRI VAN NOORDENBURG

LIENDERTSEWEG © HENRI VAN NOORDENBURG LAGEWEG © HENRI VAN NOORDENBURG

LAGEWEG © HENRI VAN NOORDENBURG BOERDERIJ © HENRI VAN NOORDENBURG

BOERDERIJ © HENRI VAN NOORDENBURG 1-Boerderij-De-Drie-Morgen

1-Boerderij-De-Drie-Morgen Who or what inhabits these places? It looks like winter: white, crisp and maybe inhospitable. There are signs of habitation: ruins of farm house and barns; remnants of fences, gates and sub-structures; farming implements; roads with marked tracks; a pile of boxes near a lone chair in one. People have lived here but is anyone still left? Van Noordenburg invites us to speculate. Maybe not the good and bad citizens who inhabit the landscapes of TV series like Lilyhammer or Fortitude, where the winter-white masks a host of indiscretions, but there is evidence of drama. Van Noordenburg explains that in the early hours of 10 May 1940, as Germany invaded the Netherlands, the Dutch army evacuated the area north of Amersfoort, destroying around 80 farms and flooding the fields to create a barrier against the approaching German army. Several of these farmlands belonged to the artist’s family and his series ‘water line’ refers to, and is inspired by, these events.

If we were there, in one of van Noordenburg’s landscapes, what sounds might we hear? Bright or somber or the muffled, near-silence of layered snow. A small insight may be this: the process of creation, he tells me, is aided, given impetus perhaps, by music, particularly that of contemporary Estonian composer Arvo Pärt, whose minimalist style and compositional technique is in part inspired by Gregorian chant. Listening to Pärt’s Tabula Rasa (one of the artist’s favorites) or Spiegel im Spiegel, it’s not hard to see a connection with van Noordenburg’s resonant images. Pärt’s evocative Spiegel has been used as a soundtrack to many films, including the 2013 lost-in-space drama Gravity, and any link between ‘Silentium’ (silence), Tabula Rasa’s second movement, and the stillness perceived in many of van Noordenburg’s landscapes may not be completely coincidental. His private world ‘contains a poetic, beautiful and intrinsic stillness… that implies silence.’² The morning of the invasion, we are told, was a still, near-perfect spring day, making it harder to conceive the events that were about to unfold.

The ‘water line’ series has led to, van Noordenburg says, a limited series of one-meter long extended compositions. It is this format and concept that currently interests him. These panoramas dwarf the original photographs that inspired them and emphasize the ubiquitous flat Dutch landscape. The broad surrounding scapes are gently desolate and subtle with minimal signs of human life, perhaps more silent and still than previous ones — but also more revelatory.

Henri van Noordenburg participated in Photo Contemporary Art Fair with the support of Queensland Centre for Photography (QCP), May 1-3, 2015, Los Angeles.

Endnotes

- Henri van Noordenburg, quoted by Aline Smithson, Lenscratch, February 1, 2013.

- Gordon Craig, in Silence (exhibition catalog), Woolloongabba Art Gallery, Brisbane, 2012.