Pop Art Design

Pop Art raised the vernacular to the level of fine art – and the vernacular returned the favor. Seeing their language and their thinking recapitulated in new stuff the art world was all agog about, the commercial and utilitarian arts reabsorbed the lessons they already knew, or thought they knew, about image and meaning. Irony, metamorphosis and recontextualization were employed as much for their wit as for their ability to disorient. To the casual grace of mid-century design, the Pop soupçon added the element of fun.

What Pop Art Design teaches us is not simply that the high and low arts locked themselves in an unyielding embrace as the modern era wound down, but that this embrace had as profound an effect on the low arts as they did on the high. The exhibition documents, among other things, how the lessons of Pop Art prompted designers in widely disparate fields – architecture, advertising, furniture, books, clothing – to look over one another’s shoulders, and to borrow ideas and icons laterally, as well as from Pop Art itself.

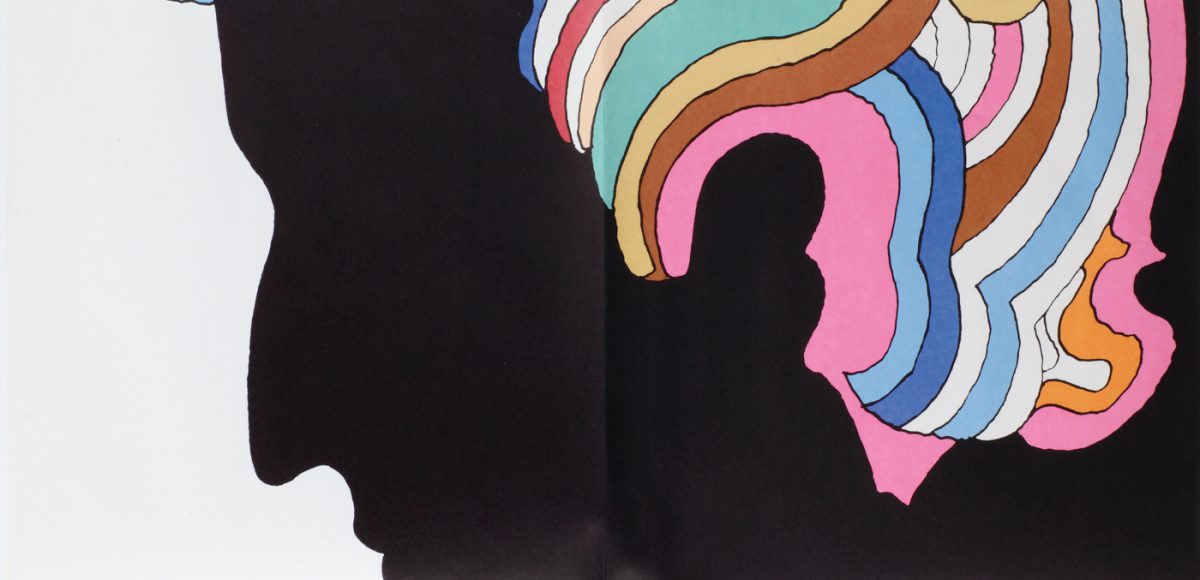

Milton Glaser (American, b. 1929). Dylan, 1966. Poster insert, Bob Dylan,”Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits“; Offset print; 83.3 x 56 cm; Columbia Records; Gerrit Terstiege © Milton Glaser. Photo: Andreas Sütterlin

Pop Art Design originated at Germany’s Vitra Design Museum and traveled mostly in Europe. Thus it is not only free of American bias – we forget so easily that Pop was an international movement birthed in England – but puts emphasis on phenomena such as the Italian design explosion of the 1960s and ’70s, a Pop-fueled efflorescence if ever there were one. Some of the funniest and most daring and surprising items in the show – a couch with an embedded American flag motif, a light the shape of its own power cord – come out of the free-wheeling studios cranking away in places like Turin and Milan. Some French and Swiss design experiments also figure in the mix; Scandinavian work, surprisingly less so. (South America and the Far East are given short shrift, betraying bias of the curators’ own.)

The home team was represented, of course, by the bulk of the “actual” art in the show. After all, it was American Pop, with its loud and lucid simplicity (and concomitant pretense at simple-mindedness), that most inspired European design. After Oldenburg, after Lichtenstein, everyone knew what to do. But proper homage is paid two of America’s most important architecture-and-design couples, Charles and Ray Eames and Robert and Denise Scott Venturi; both their concepts and their achievements in the postwar years made Pop itself not simply possible, but necessary. By the same token, however, Alison and Peter Smithson, the London couple at the conceptual heart of the proto-Pop Independent Group, are thrown in with all the other “merely” visionary architects, from Buckminster Fuller on down. Clearly, the emphasis of the survey was more on things and less on ideas – appropriately enough, given the nature of Pop and its impact on vernacular culture, but leaving the show itself to seem a bit vacuous.

In fact, it was one of those surveys that makes more sense in a book than it does on the wall, no matter how many striking images and objects might be arrayed. Indeed, the practical as well as conceptual connections between the things in the galleries are best elucidated in the catalog. The catalog also reveals that not everything in the original show made it across the pond; even as it filled OCMA’s copious space, the exhibit, grouped logically enough according to various rubrics, was uncomfortably designed, jumping from expansive and entertaining displays of lamps and chairs to semi-contained darkrooms in which vintage slides and film projections opened up the documentary projects of pioneers like the Venturis. By time it hit these shores, Pop Art Design had lost some of its fizz. It left you more curious than when you came in, a Mad Men campaign compromised by European circumspection. But that only made you want to buy the catalog more – a successful subliminal pitch.