Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage

(July 31, 2017—January 7, 2018)

Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage, a collaboration between the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, was curated by LACMA’s Stephanie Barron in collaboration with opera director Yuval Sharon. The exhibition vividly reflects Chagall’s passion for music and dance. The display of extravagant costumes and stage sketches recalls a similar dance-and-music oriented survey, the Oskar Schlemmer retrospective Visions of a New World, at the Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart, Germany, two years ago. Several similarities and overlaps provoke the association between Chagall and Schlemmer, such as their stage works for ballets by Igor Stravinsky, and the fact that both artists were persecuted by the Nazis. Yet, at a preview of the exhibit, Chagall’s granddaughter Meret Meyer said, “The two didn’t know each other personally.” So, it’s not clear if there was any cross-influence. What is certain is that both painters embraced interdisciplinarity and gave the performing arts a modern twist.

Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage is not arranged in strictly chronological order, but is emotionally and aesthetically driven, accompanied by classical music from the four productions on which Chagall worked: Aleko, The Firebird, Daphnis and Chloe and the opera The Magic Flute. Also noteworthy is the fact that the exhibition follows a narrative in which love plays a key role. All four productions Chagall worked on center around the theme of love; and all are driven by Chagall’s love for the performing arts. As he once said, “Only love interests me, and I am only in contact with things that revolve around love.”

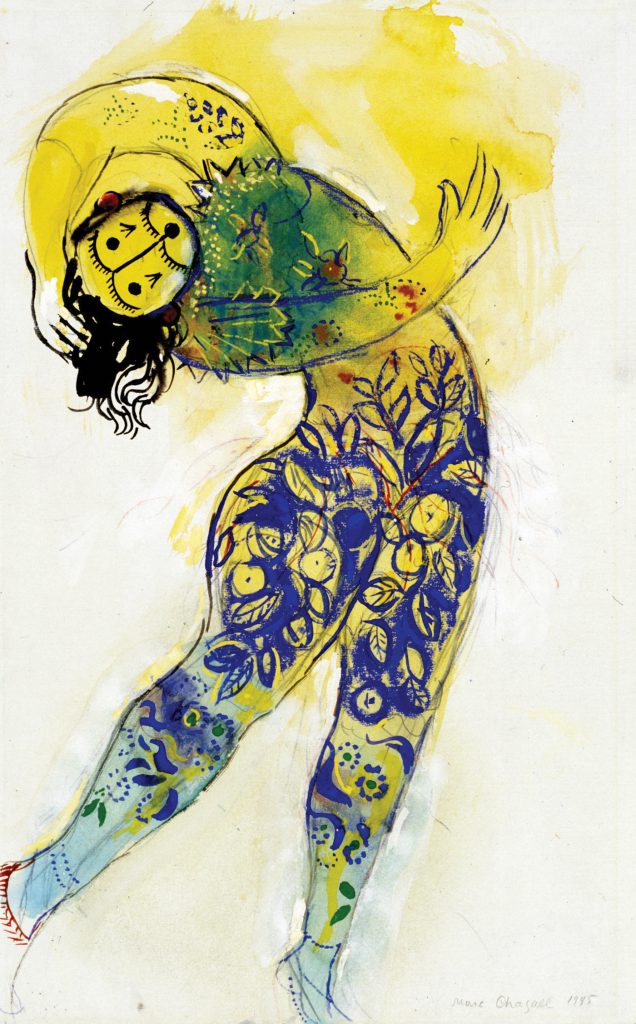

Marc Chagall, Costume Design for The Firebird: Blue-and-Yellow Monster from Koschei’s Palace Guard, 1945, watercolor, gouache, graphite and india ink on paper, 18 5/16 x 11 7/16 inches, private collection, © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris, photo © 2017 Archives Marc et Ida Chagall, Paris

Marc Chagall, Costume Design for The Firebird: Blue-and-Yellow Monster from Koschei’s Palace Guard, 1945, watercolor, gouache, graphite and india ink on paper, 18 5/16 x 11 7/16 inches, private collection, © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris, photo © 2017 Archives Marc et Ida Chagall, Paris Installation Photograph, Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, July 31, 2017–January 7, 2018, © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris, photo © Fredrik Nilsen

Installation Photograph, Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, July 31, 2017–January 7, 2018, © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris, photo © Fredrik Nilsen

The show begins with Chagall’s backdrop studies and costumes for the ballet Aleko, based on Alexander Pushkin’s poem The Gypsies, choreographed by Léonide Massine and set to Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Trio in A Minor. There are also film excerpts from the 1942 production in Chagall’s adopted city, New York. The premiere was supposed to take place there, but, due to union policies, the artist was prevented from completing his work in New York, so the entire crew went to Mexico to finish. Consequently, the ballet premiered at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, the costumes displaying a mélange of Russian, Jewish and Mexican influences: In his costumes particularly, Chagall relied on both his familiar motifs (animals, fiddles) and forms and images from the Mexican traditional dress. The various fabrics, from taffeta to georgette, were chosen by his wife Bella, who selected them from Mexican markets.

Also featured is a display of stage sketches from two other ballets in which Chagall was involved: Stravinsky’s The Firebird and Maurice Ravel’s Daphnis and Chloe. The former debuted at the Metropolitan Opera House in 1945, the latter at the Paris Opera in 1959. Especially noteworthy are the fantastic, partially embroidered costumes for Firebird, made a year after Bella’s death, presenting anthropomorphized demons, monsters and animals mounted on rotating stage platforms so that viewers can see them from all sides. Prime among these is the elegant costume with a blue fruit tree ornament for the Blue-and-Yellow Monster from Koschei’s Palace Guard.

The stage display ends with Mozart’s Magic Flute, the only opera Chagall ever worked on, which premiered at the Met’s Lincoln Center home in 1967. Here, Chagall shifted from pure drawing to collage, most evident in a bird cutout and pieces of shimmering gold and fabric integrated into the sketches and costume studies. The sash around Pamino’s waist and the head cover on Sarastro epitomize mysteriousness. Comical are the suggested feathers on Papageno and Papagena’s costumes, underlining Papageno’s duties as a bird-catcher.

A separate, much smaller part of the show addresses Chagall’s engagement more generally with the performing arts. This addendum includes videos of discussions by experts about the merging of the fine and lively art forms. It closes with a few iconic Chagall paintings displayed in a separate area. Among them are The Green Violinist (1923-1924) and Self-Portrait with Seven Fingers (1912), emphasizing both Chagall’s love for music and his affinity for his adopted home of Paris, the city of love.