Rain, Rain, Go Away…And It Does

A chat with Florian Ortkrass and Hannes Koch, creators of Rain Room, LACMA’s new exhibit that simulates a rainstorm.

Where does it rain, but you never get wet?

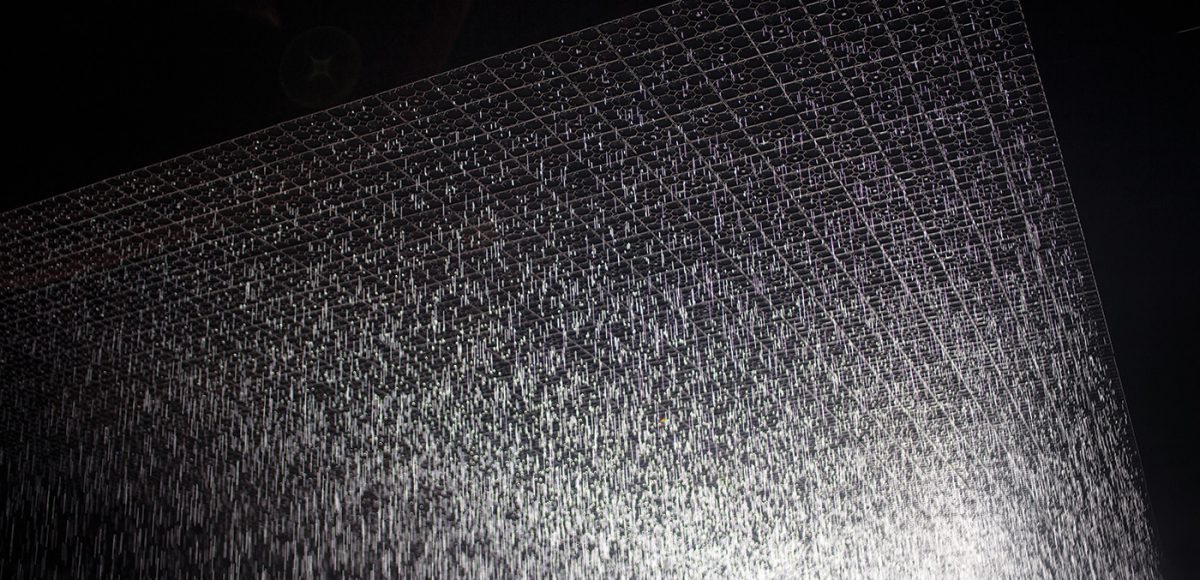

Although not a riddle, the Rain Room exhibit at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) might prompt a guffaw, or at least a grin. Created by Random International, a collaborative studio for experimental practice within contemporary art in London, the multi-sensorial installation, illuminated by a singular light source, simulates an indoor downpour. But here’s the catch: walk into the storm and, via sensors, it stops overhead but continues elsewhere. An ethereal experience that elicits childlike awe, Rain Room is one of the most profoundly moving (and selfie-photo-inducing) L.A. art installations of the year. Although not a new Random International concept (its first version was mounted in 2012), each Rain Room is different in size and configuration.

We caught up with the heads of Random International, Florian Ortkass and Hannes Koch—known for installations that meld technology, science, architecture and nature—to understand their inspiration behind the project and discover what’s next. (Spoiler alert: robotics!)

Rain Room by Random International (2012). Rain Room at Yuz Museum. Photo: Delia Keller

Fabrik: Your first Rain Room was mounted at the Barbican in 2012. How many Rain Rooms have been shown since then?

Florian Ortkass/Hannes Koch: Since the exhibition at the Barbican, it has been shown at the Museum Of Modern Art, New York (2013), the Yuz Foundation in Shanghai (2015), LACMA in Los Angeles (until 6 March 2016), and will be permanently installed at the Sharjah Art Foundation (2017).

Why rain, instead of some other type of weather?

For us, Rain Room was less—or actually not at all—a project about the weather. Rather, we see it as an investigation of the countless artificial and mechanized environments and systems that are omnipresent in life today—some of which humankind can more or less control, and some of which control humankind completely. The studio is interested in the reaction to such systems and environments, and how they can go undetected even whilst being used on a daily basis. Then there is that ephemeral quality of rain and trying to recreate it.

How is the LACMA installation unique?

There is a slight geometric reconfiguration. Whereas previous Rain Room iterations have been rectangular, at LACMA, the field of rain is in the form of a square. From the initial concept, this has been something we wanted to investigate, but we never had the space to do so until now. But for us, the most intriguing part of the exhibition begins when the setting-up process ends, once the first visitor enters the piece in a new location and a different context.

Here in L.A., drought is at the forefront of everyone’s mind, and it seems to be the first connection that is made when they experience the piece. We somewhat expected this, the drought being such an immediate part of life for everyone in the city, but the extent of it is crazy. For some of the kids visiting the piece, it is the closest they have ever come to experiencing rain in their lives! For children to see rain for the first time inside a museum… Of course, they then try to get wet. In a sense, this offers a dark, sci-fi view into a future where it is not only animals that are preserved though captivity but also natural phenomena—all of which we now take for granted as “available.”

In this context, Rain Room could also be seen as a reflection of individual impact—and the accumulation of this impact—on environments. There could be a hundred people inside Rain Room but, by principle of the piece, there just wouldn’t be any rain…

Speaking of drought, Rain Room uses approximately 528 gallons of water (for perspective, the average American family of four uses 400 gallons of water per day). Is it recycled?

From the very first instance, when we were initially considering how this piece could be realized, we knew we wanted to recycle the water. There was never any question about this. The water is collected, filtered, treated and tested while it’s being cycled. It was actually one of the most difficult problems to solve. Typically, in the studio, we learn as we go; for most things we want to do, knowledge has to be learned from scratch. This involved a lot of experimentation, testing, and tuning with the final piece in situ.

Is there a message for Angelenos on the topic of global warming/water use you’re trying to communicate?

If we have a message, it is not only to Angelenos, but also to all of us. Our hope is that Rain Room can offer a space for contemplation and an amplification of conversations surrounding the relationship between man, machine, and environment. Everything we do has an impact. Art has a unique capacity to question generally accepted and established ways of doing things, and to prompt new questions.

What is it about the Rain Room experience that elicits such strong reactions of joy?

As a child, you play in the rain. Then, as you grow into adult life, it simply becomes a nuisance when you’re on the way to work. We get used to things and take them for granted so easily. When there is indoor rain that can’t be touched, maybe the surreal quality creates some space from the familiar.

And why do you think it has such lasting power that droves still attend, even though it’s been a phenom for more than three years? (LACMA tickets are already sold out!)

It is a very open work. Everyone has their own experience and can find their own interpretation, but at the same time it evokes something in the collective consciousness.

You founded Random International in 2005. Over the last 10 years, what RI project are you most proud of, and why?

Audience (2008) is one of our earlier works, and in some ways it is very simple. There’s a hoard of small rectangular mirrors mounted on cast iron bases that are very subtly animated to behave as though they are living. Their form doesn’t really represent any type of living being, but through nuances of their movement, they are perceived as such; people always refer to the mirror units as ‘little guys’ or something similar. Creating Audience, resolving the tiny refinements that make or break the piece being perceived as someone “alive,” marked a crucial point in the studio. It prompted us to ask some big questions about how the human mind perceives motion and how little information it needs for the recognition of natural forms. These questions remain at the core of the studio’s research, and we just keep on digging deeper.

When Rain Room was first exhibited at the Barbican in 2012, it was a huge moment. Although it was four years in the making and had been prototyped and tested, there were so many unknowns—public reaction being the largest. Maxine and Stuart Frankel (who originally commissioned the work) and the wonderful team at the Barbican took a massive leap of faith with us. None of us could anticipate the queues and selfies that were to come. It was an experiment. Then, Tower at the Ruhrtriennale (2013) was quite something to witness. Using water as the material to make a 20-meter high building within the epic Zollverein [a former industrial complex, now World Heritage site, in Essen, Germany] was quite a feat. There is no tracking in Tower. The walls of water appear and disappear instantaneously and no water falls directly at the center of the structure. But that gentle, meditative aspect of protection you can get in Rain Room is totally absent. Tower is elemental.

Can you talk about the working relationship between you and your partner in creating projects for Random International?

We are very different from one another. We share the artistic direction of the studio, both in terms of the conceptual—partially choosing a deliberate ignorance of what implications a certain decision might have—and the realization process, where we can be very pragmatic. It usually starts with one of us two bringing an idea, or the start of one, to the table. The selection process is harsh. Going live, together with the team, we then split up the roles necessary to bring an idea to life, including technical development, communication, financing, and production development.

Which future projects are you most excited about?

We’ve been working with a biomimetic robotics lab at Harvard, and the research has led us down a fascinating path which we continue to explore with new works in development. Then, working with Max Richter on concepts for the durational performance aspects of his incredible work Sleep is simply extraordinary. Increasingly, we are working in the public realm, which is both exciting and intriguing. In recent years, we’ve also stepped up the research aspect of the studio, and there is a lot of internal anticipation surrounding our next studio symposium.

If you had all the resources/time/technology/superpowers at your disposal, what kind of project would you do?

That’s a dangerous question… Introduce tax relief for civil courage and good humor. Or set a competition to formalize successful alternatives to Capitalism (ideally the prize still has value by the time we have a winner)…or not.

What other artists in your technology-meets-experiential art genre inspire you?

Ideas come before technology. Way back, the tools and materials were not always readily available for people to realize what they wanted to, but they still managed. Those artists who were early participants in LACMA’s original Art & Technology program, the proponents of the Light & Space movement, they are inspirational in their attitude and approach. Those who have a more direct inspiration to the works? Roboticists, neuroscientists, biologists – nature.

Besides your own, what’s the most life-altering art exhibit or other creative performance you’ve been to and why?

Birth of my first child. [Florian Ortkass and Hannes Koch both have children and concur it was the most profound creative event of their lives.]

RAIN ROOM at Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art (LACMA)

5905 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles CA 90036

Through March 6, 2016More information can be found on Random International’s website at:

www.randominternational.com_

Images: Courtesy of Random International