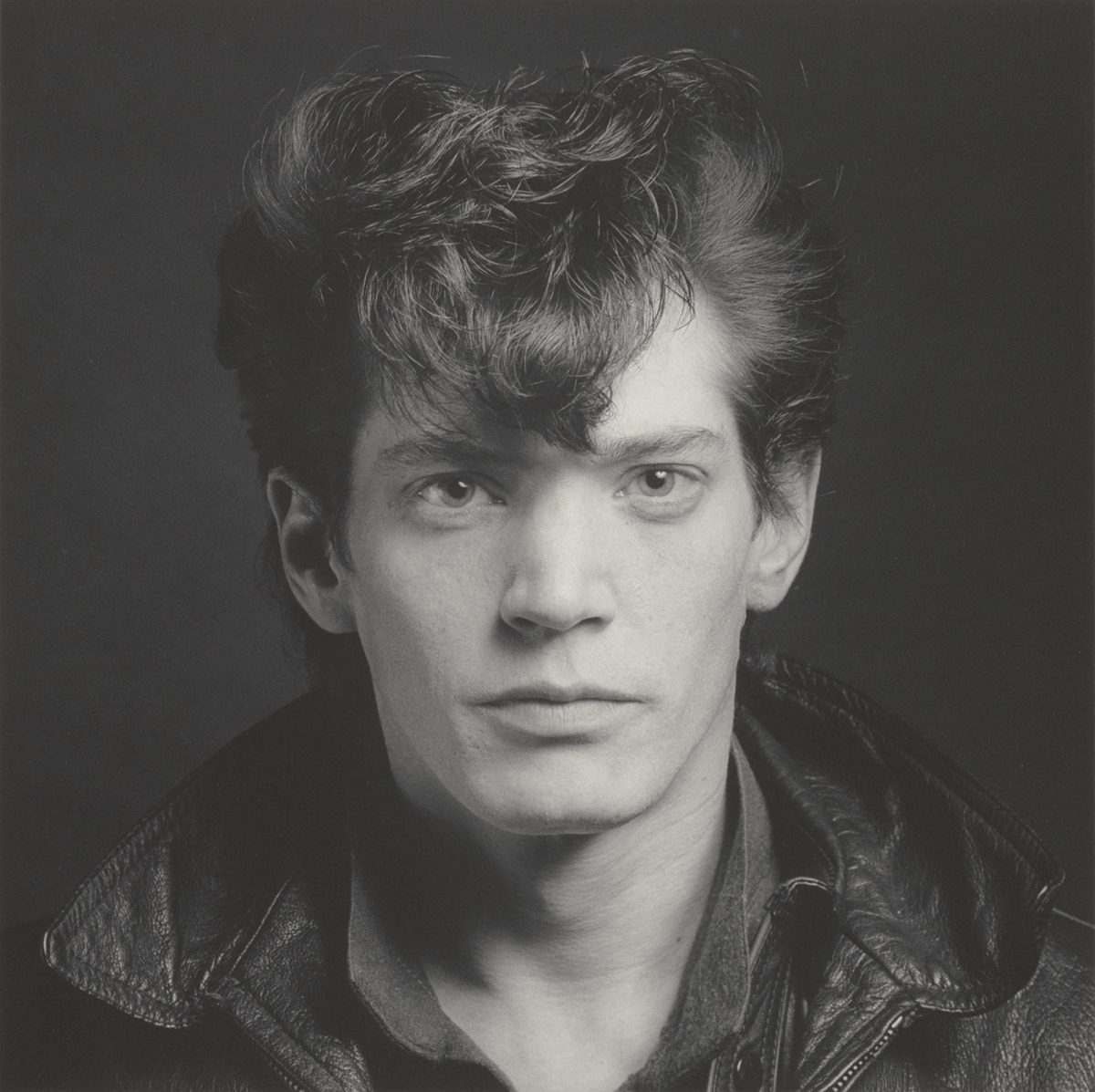

Aging, a fact of life especially hard to conceive of when young or youth-obsessed, encroaches on a cessation of activity. Even so, the portraits and stories evident in Peterson’s compelling series entitled ONE HUNDRED immerse us in the visible grace of tenacity. Faces and bodies, literally inscribed by one hundred or more years, meditatively emerge through this still evolving body of work. These photographs suspend and reflect an ageless consciousness gained entirely from Peterson truly seeing these particular individuals. In turn, she casts us as witnesses to their endurance.

As life expectancy increases around the world, people who live for one hundred or more years reveal they are in possession of the untapped wealth of actual experience, which is readily being dissolved in favor of increasingly hyper-digital environments.

The inexplicable comfort of surviving a century challenges such a virtual complacency. Peterson curbs time itself by regally foregrounding age within the felt gratitude sight and then vision embody simply by placing her portraits of lives still being lived before us. To do so, she embarked on a formative expedition throughout the Americas, including twenty-five states in various regions of the United States, several provinces in Canada, and even into a Mayan village in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. Finding ONE HUNDRED centenarians to share their agile presence became formative for her, personally as well as professionally. Fabrik celebrates her journey with the Q&A below.

How did this journey to bear witness to the grace in aging begin for you?

It began with my grandmother Cecile. She lived to be 101 years old; she was a great support to me growing up. I asked one of the nurses at her facility if there were any other 100 year olds there, and if I could meet them.They introduced me to Mary. She was so excited to have a visitor, her eyes lit up and the stories just came pouring out. I realized then that this was a project I had to do.

What in your outlook on creativity has changed most noticeably since embarking on this particular series, which has been many years in the making and is still on-going?

Continue to make the time and energy to do the projects that are fulfilling. It’s important for me to create work that has a positive impact on people. It was clear while working with the centenarians how much they and the people around them enjoyed being part of the project and sharing their lives. It’s also inspiring to see the centenarian artists still creating work and doing shows. It puts my mind at ease to know that I may create until I die.

How do you find the centenarians you photograph?

At the beginning, I researched online and visited various facilities much like the one my grandmother had lived in. It was very challenging at first. If I was lucky, I found one centenarian per month who was willing to work with me. Slowly over time, word of mouth spread and I began to build trust. Then, after a very fortunate interview with Slate, people began contacting me about centenarians close to them.

Los Angeles being synonymous with youth, in a sense, how have people you know here, as well as elsewhere, responded to the nature of this work/series.

We are all aging, and people tend to respond to my project in the same way they are responding to that simple, inevitable fact of life. I would say the emotional response has been mostly hopeful, because it’s inspiring (to some) to think that they might live a long life, too. The quality of many of my subjects’ lives is quite good, and that gives people hope for the future. It’s comforting.

Can you share how you approach staging your portraits, which appear naturalistic yet transparently reveal both the subject’s presence as well as your own, with subtlety and intention?

When I arrive at each location, I observe how mobile they are and what they are capable of doing. I find two to three locations within their space that seem to capture what’s important to them, and then I find another location to shoot a close-up. I light their environment to mimic or highlight the lighting that already exists. As I photograph, I direct them to look in different directions but also let them relax into their posture. It’s important that they be themselves and look their best.

Has photographing this series led you to view how to pass time differently?

I have realized how vital human interaction is, how important it is to stop and have fully present moments with other human beings.

You also found yourself in a Mayan village in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula for this series. How did that environment change and/or inform your approach and perspective of the individuals you encountered there?

I went with a really close friend of mine who speaks Spanish fluently. We had a goal to have as much fun as possible while finding as many centenarians as we could. I just rented a car, threw in my camera and lighting equipment, and drove to different Mayan pueblos. We simply asked people if there were any centenarian residents. We ended up going to about 6 different pueblos and photographing 12 centenarians. The Mayan people we met were so friendly and welcoming. We would get to their door and they would instantly invite us in.

How do you envision this series best being seen? What are your hopes for its exhibition?

I envision large framed prints. I’d like a button of some kind that you could press to hear a centenarian say his or her name, age, and where he or she was born. Perhaps this could be a accompanied by something written, as well. A piece of dialogue or a fact of their lives.

In all your encounters with close to 100 centenarians, did you perceive a common thread or “secret,” so to speak, to their having lived as long as they have?

It’s interesting, I kept thinking I would learn some secret to longevity, about why some people live for a long time and others don’t. But they all lived their lives so differently: some have great genes, while others are clearly an anomaly in their family, some smoke and drink daily, others are extremely health-conscious, some pray and have a great deal of faith, others have a cynical world view. There were no consistent reasons across the board for their long lives. It confirmed for me that there’s no one way to live, and to just keep living intuitively, in the way that feels right for me.

What do you love about living and working in Los Angeles? How does your experience in this city inform your work?

I feel free in Los Angeles. Interesting, beautiful locations are within driving distance. The weather makes it easy to live and find inspiration.

Robert Frost once wrote, “The afternoon knows what the morning never suspected.” Similarly, the magnificent people portrayed within Peterson’s ONE HUNDRED appear to intend their lives and defeat the many misconceptions we associate with aging.

For a more visceral experience of the portraits within her series, two prints entitled The Twins and Naomi was on view at Santa Monica Art Studios in Arena 1 as part of the MOPLA (Month of Photography LA) Group Show in May of 2015. Organized by the Lucie Foundation and curated by Meredith Marlay, the submission based exhibition is designed to support the 2015 theme Realities and Concepts. The group show features emerging and established photographers.

In the near future, Sally Peterson intends to publish ONE HUNDRED in book form as well.

To learn more about her work or volunteer participants for her project, please visit www.sallypeterson.com.