On the occasion of his 30-year survey at Santa Monica College Pete and Susan Barrett Gallery

(February 14-March 25, 2017)

To say the paintings of Andy Moses are works of beauty is both a self-evident truth and an oversimplification. They are not beautiful in a fleeting way, like a one-night stand — alluring at midnight but expendable at sunrise. Instead, their beauty is grounded in years of experimentation in the chemistry of paint and a devotion to the physics of gravity and light. It is a beauty attained through an unyielding determination to push the underlying science and vision to new levels. Rooted in a curiosity about the natural world, the paintings of Andy Moses are the result of observation as much as the mastery of a meticulous process.

The artist’s recent mini-retrospective at Santa Monica College Pete and Susan Barrett Art Gallery offered an overview of painting from the last three decades, beginning with work Moses produced in New York during the 1980s. The exhibit chronicles the evolution of his palette, from black-and-white to riveting color, and conceptual arc, from two-dimensional works to sculptural paintings with curved surfaces that leverage light with scintillating impact.

Andy Moses. R.A.D. 1704, 2017. Acrylic on polycarbonate, mounted on parabolic, vertical concave wood panel, 70 x 93 inches

Andy Moses. R.A.D. 1704, 2017. Acrylic on polycarbonate, mounted on parabolic, vertical concave wood panel, 70 x 93 inches Andy Portrait Geomorph

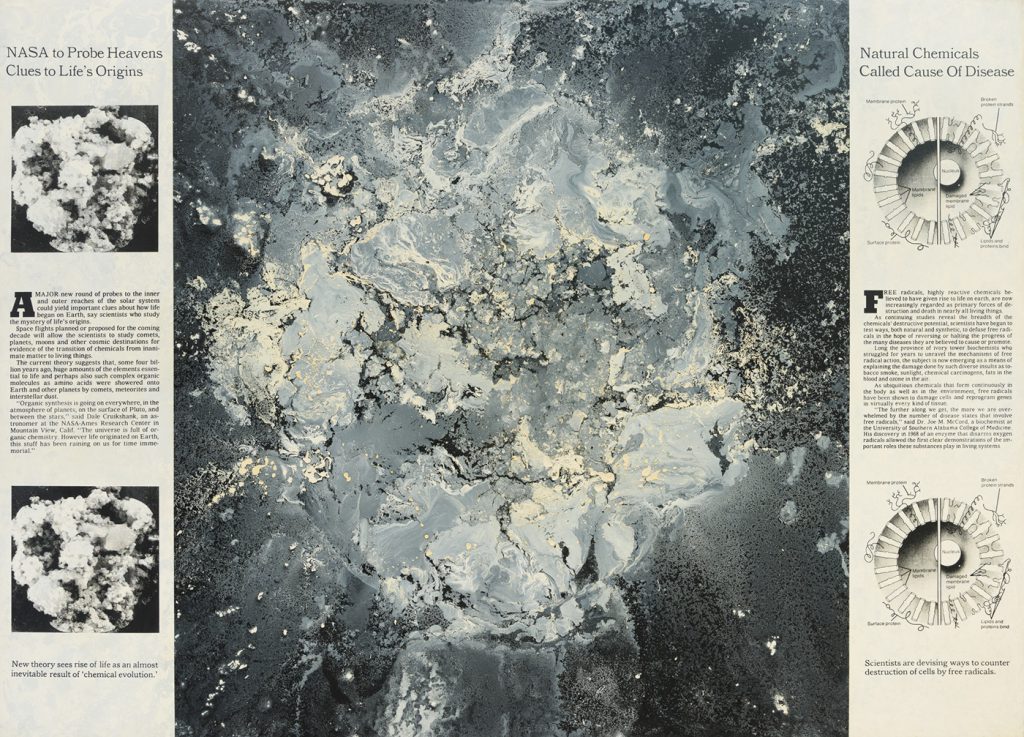

Andy Portrait Geomorph Andy Moses. NASA to Probe the Heavens Natural Chemicals, 1988. Acrylic, alkyd and silkscreen on canvas, 65 x 90 inches.

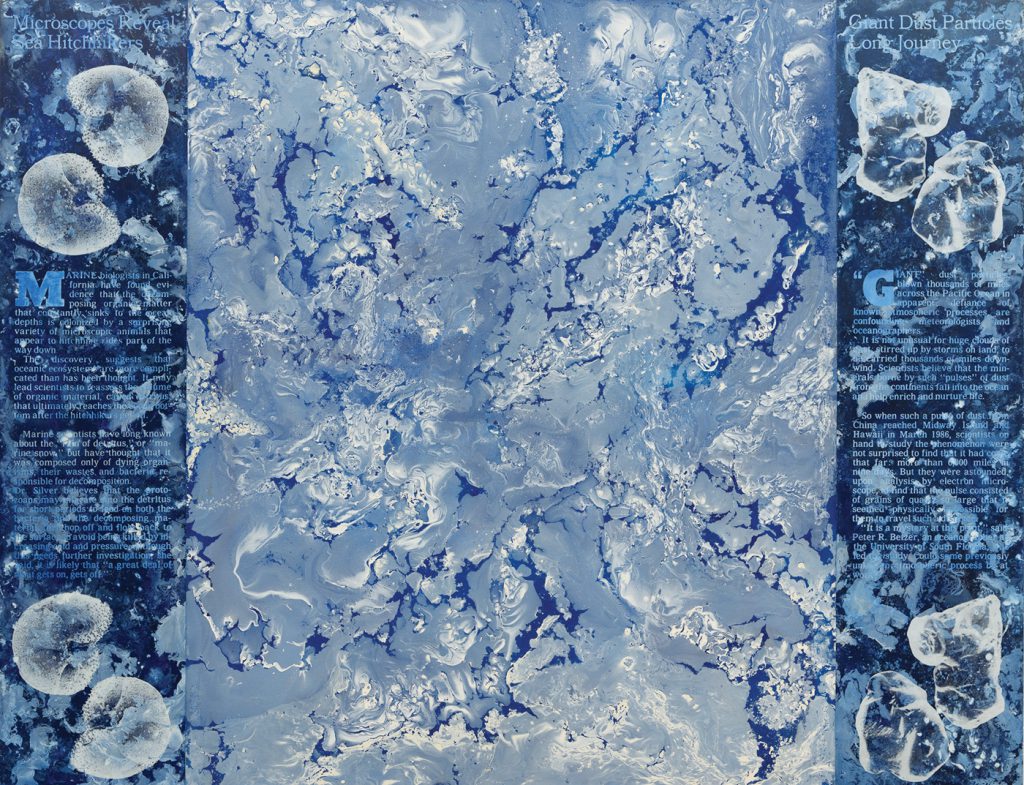

Andy Moses. NASA to Probe the Heavens Natural Chemicals, 1988. Acrylic, alkyd and silkscreen on canvas, 65 x 90 inches. Andy Moses. Sea Hitchhikers Long Journey, 1989. Acrylic, alkyd and silkscreen on canvas, 60 x 78 inches.

Andy Moses. Sea Hitchhikers Long Journey, 1989. Acrylic, alkyd and silkscreen on canvas, 60 x 78 inches. Andy Moses. Veil of time, 1986. Acrylic and alkyd on canvas, 60 x 90 inches.

Andy Moses. Veil of time, 1986. Acrylic and alkyd on canvas, 60 x 90 inches. Installation View. Santa Monica College, Pete and Susan Barrett Art Gallery.

Installation View. Santa Monica College, Pete and Susan Barrett Art Gallery. Installation View. Santa Monica College, Pete and Susan Barrett Art Gallery.

Installation View. Santa Monica College, Pete and Susan Barrett Art Gallery. Installation View. Santa Monica College, Pete and Susan Barrett Art Gallery.

Installation View. Santa Monica College, Pete and Susan Barrett Art Gallery.

His curiosity about science didn’t vanish when Moses became a painter. The early black-and-white paintings in particular are derived directly from scientific themes. Many of these paintings feature a sort of enigmatic rock or one-cell, amoeba-like subject. Moses also used the weekly New York Times Science page as a back- ground for a series of mixed-media works in which astronomy, geology, medicine and marine biology were catalysts for composition.

When he moved back to California from New York in 2000, Moses discov- ered a new quality of light. “I had a studio in Venice where light flooded in. I’d never had a studio like that — even in Montauk. It’s not like California light. It’s different.”

During this time, Moses was concentrating on his white paintings, luminous works, such as the aptly titled tondo, Enigma (2003), with its swirling pearlescent white forms. After leaving one of these paintings leaning against a wall in his studio at the end of a day’s work, he returned the next morning to find it dramatically lit, its slanted angle catching the light obliquely off the surface. This epiphany prompted the idea to paint on a curved surface, deliberately optimizing the effect. The curved paintings followed — often panoramic, variously convex and concave. The harnessing of light also led to the incorporation of color. Moses’ palette became increasingly saturated with high proportions of iridescent and interference colors to maximize vibrancy — again capitalizing on light. The curved surfaces also had the effect of making the iridescent elements shift as the viewer moved. “I’ve always wanted imagery that looks like it’s moving or shifting or changing, like you’re catching a moment,” Moses said. “And then a moment later, it’s something else. Nothing is fixed.”

“Beauty, like truth, is relative to the time when one lives and to the individual who can grasp it.” — GUSTAVE COURBET

“The power of beauty at work in man, as the artist has always known, is severe and exacting, and once evoked, will never leave him alone, until he brings his work and life into some semblance of harmony with its spirit.” — LAWREN HARRIS

“Why should beauty be suspect?” — PIERRE-AUGUSTE RENOIR

While truly abstract, even the more recent gravity-flow paintings still allude to representational elements — or more specifically, elements and forces of nature. The works could be construed as referring to landscape or planetary forms viewed from space — or conversely, a macro view of a small thing like an extraordinary variegated rock. There is an assertive physicality to the way his process — pouring acrylic paint of various viscosities in a strategic and controlled way — harnesses the natural flow of gravity, while something of the essence of nature is captured and reflected in the finished work.

Gradually, linear marks that evolved from a reference to the horizon were replaced by echoing serpentine lines, like the pattern of marbled Florentine paper (which Moses was thrilled to discover on his first trip to Florence). In a satisfying way, motifs and approaches Moses began exploring 30 years ago continue to be developed, refined and synthesized in his work today. His oeuvre comes full circle as the rock form, so prominent in the early years, reappears. Moses brought back the rock, or as he calls it “the blob,” as the predominant subject of Metamorph 1502 (2016). Then, in a daring act, he took it a step further with Geomorph 1504 (2016). What would have been a fully resolved horizontally-oriented gravity-flow painting was reassigned to the background as Moses superimposed a stunning rock-like form in the same palette, fiery red oranges and blues, in a vertical configuration in the foreground. The underlying painting could have been ruined if the attempt failed. Moses said, “It has elements of everything I’ve done up to now, and want. It’s the culmination of so much work and research.”

All the experimentation, the exacting process, the leveraging of color and light, are propelled by one overarching objective: the manifestation of beauty. “It’s a huge driver in my work. It’s what I strive for. But I want something that’s mesmerizing — beautiful and complex as well,” said Moses.

True beauty is dramatic, he added. “I want that kind of drama. Something that’s arresting, that stops you in your tracks. If something isn’t really stunning, if it doesn’t stop you with its beauty, for me, it’s engaging to a point, but it can never take me as far as I want to go.”