The late 20th-century black-and-white documentary-style portraits of contemporary photographer Roger Ballen are simple, classic and elegant. His square format and tight compositions define an alien cosmology of post-apartheid, poor white Afrikaners living in the countryside of rural South Africa. These outlanders exist in a flat zone. Here, time, culture, disease and a certain amount of genetic familiarity, breed a strange brew of inhabitants. Born in 1950, Ballen grew up in Westchester, a suburb of New York City. His mother was an assistant to several photographers at Magnum Photos. In the 1970s, she co-founded the gallery, Photography House. Ballen got his first camera when he was 13-years-old. He studied psychology at the University of California, Berkeley and after receiving a PhD in mining and engineering, he moved to Johannesburg in 1982 and began photographing the South African underclass.

Like Diane Arbus, Ballen photographs his subjects with a genuine affection that adds a sweetened layer to their raw authenticity. “I didn’t look at these people as extraordinary or different, I just saw them as … other human beings walking the planet, that’s all… No more… No less,” Ballen said in an email interview with Fabrik. “I liked them a lot more than the people in shopping centers pretending they’re more important and better than anybody else.”

Roger Ballen 2016

Roger Ballen 2016 Roger Ballen. Head Inside Shirt, 2007

Roger Ballen. Head Inside Shirt, 2007 Roger Ballen. Liberation, 2011

Roger Ballen. Liberation, 2011 Roger Ballen. Take Off, 2012

Roger Ballen. Take Off, 2012 Roger Ballen. Headless, 2006

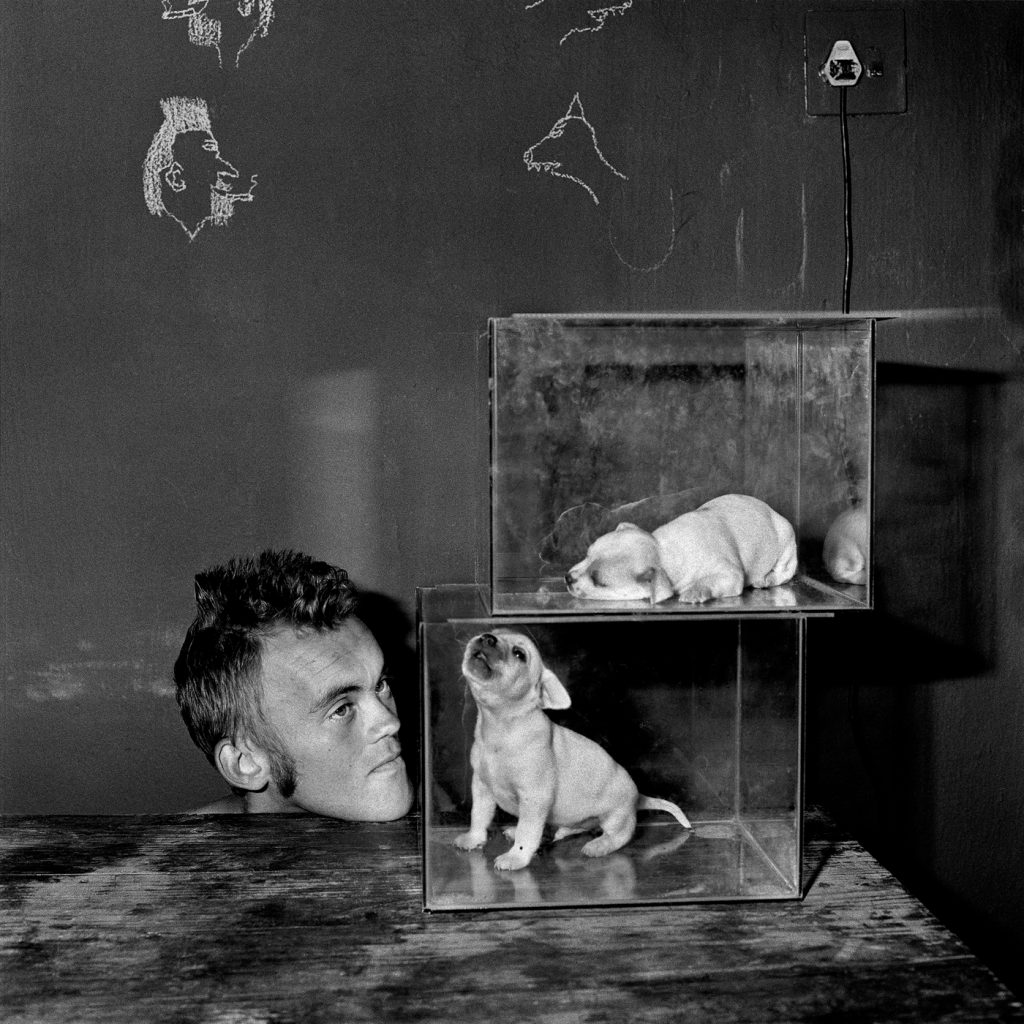

Roger Ballen. Headless, 2006 Roger Ballen. Puppies in Fishtanks, 2000

Roger Ballen. Puppies in Fishtanks, 2000 Roger Ballen. Brian with Pet Pig, 1998

Roger Ballen. Brian with Pet Pig, 1998 Roger Ballen. Puppy Between Feet, 1999

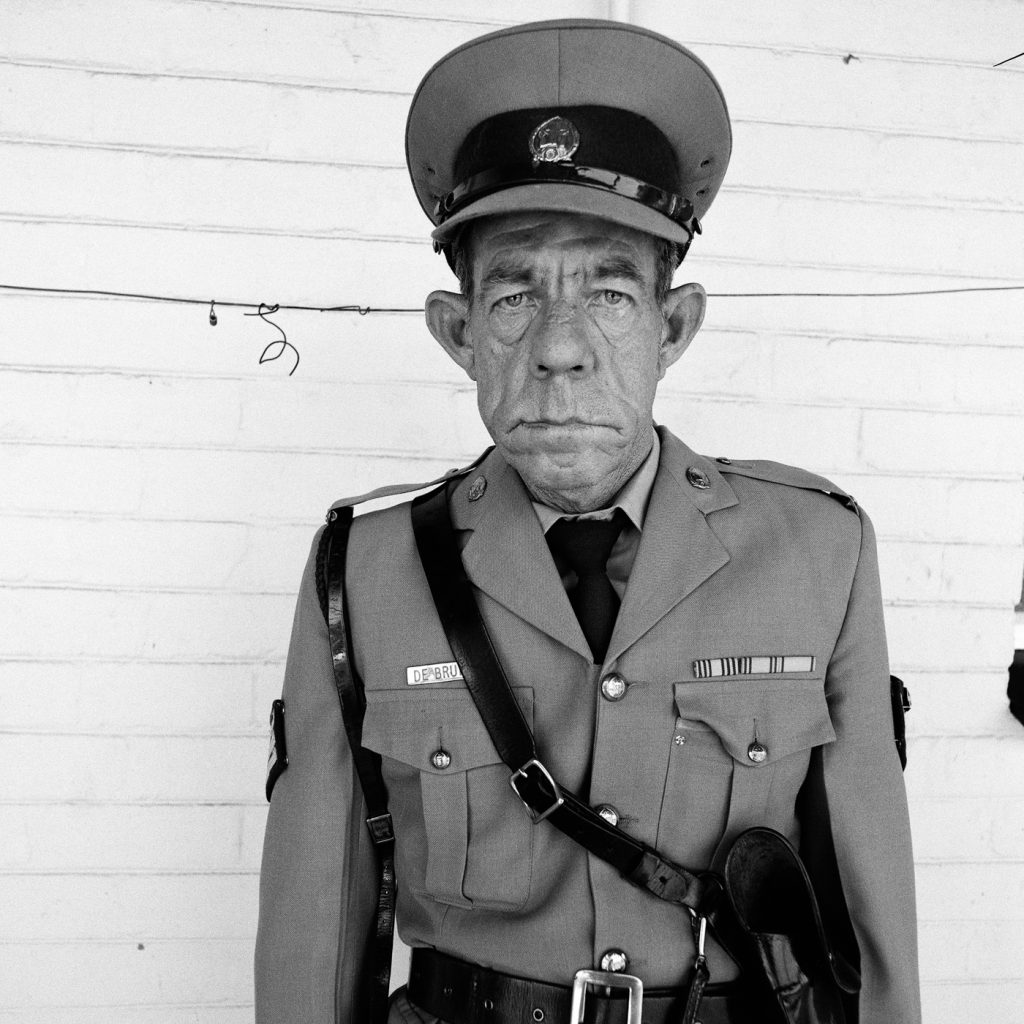

Roger Ballen. Puppy Between Feet, 1999 Roger Ballen. Sergeant F de Bruin, Department of Prisons employee, Orange Free State, 1992

Roger Ballen. Sergeant F de Bruin, Department of Prisons employee, Orange Free State, 1992 Roger Ballen. Dresie and Casie, Twins, Western Transvaal, 1993

Roger Ballen. Dresie and Casie, Twins, Western Transvaal, 1993

Later on in his career, the artist began experimenting with video. “I Fink U Freeky,” Ballen’s video collaboration with Die Antwoord, a South African rap-rave group, offers insight into his approach to photography. In the video, the band’s singer, Yolandi Visser, a dirty-strange, blonde siren of a performer, writhes lasciviously atop a pile of fat, furry white rats. “There’s an interesting relationship between my photographs and what Die Antwoord did,” said Ballen. “I think it’s useful to try to show how photography can be transformed through video.”

A number of Ballen’s videos can be viewed on his YouTube channel. There, the film, “The Theatre of Apparitions” is described as “an animated theater of dismembered people, beasts and ghosts [that] dance, tumble, make love and tear themselves apart: A nightmarish subconscious world in black-and-white.” “The Theatre of Apparitions” has bizarre sequences that leave behind traditional filmmaking and photography, and parody high art. The images are painted, drawn, then animated in a way that might have been done during the late Middle Ages, when art, dance and music mocked sex, death and the Black Plague.

Another of Ballen’s films, “Roger Ballen’s Theatre of the Mind” is charac- terized in its YouTube summary as “a psychological thriller set in a zone between sanity and insanity, dream and reality,” This work plays with conscious and subconscious stories that seem familiar, yet are distinctly odd and scary. Many of the actors, plucked from real life, have grotesque faces, and missing or filed-down, pointed teeth. They inhabit surreal, derelict buildings, teeming with black and white rats. (Ballen has said he believes rats are the smartest species on the planet in relationship to their brain size.) A skinny, shirtless, filthy man is a Jungian pied piper. He gathers the rodents into a misshapen cloth rucksack that he hoists over his shoulder as he skitters through a barren, Ballenesque cityscape. Often, these ruins have the artist’s drawings sketched onto the walls. Some make sexual references, others have disembodied, primitive faces.

These works shimmer with inscrutable enigmas and the offbeat metafictions of mutant fairy tales. They are foreboding territories. Strangely compelling models, posed as if their bodies have been dismembered, enjoy a playful, endearing perversity. Scary meets sexy. Black meets white. Swirled against tableaux that are sculpted with wires or drawn with charcoal, Ballen enacts his dark, dreamy Freudian rituals. These theatrical performances repurpose people, birds, puppies and kittens as objects to be juxtaposed in unsettling ways, then set up and starkly shot.

Ballen’s psychological sojourns are caught up in a delightfully demonic, playfully perverse state of bliss, full of mystery, transformation and constant evolution. The photographer said he hopes his work “…will continue to transform people’s psyches in a positive way, assisting them to bring together disparate parts of their selves into a more unified state of being.”

Publications include: Platteland: Images from Rural South Africa (1994), Outland (2001), Shadow Chamber (2005) and Boarding House (2008), published by Phaidon Press. Later this year, Thames and Hudson will publish Ballenesque, a 50-year retrospective documenting Ballen’s aesthetic development.

Ballen’s work is represented in international museum collections including the Bibliothéque Nationale and Centre Pompidou, Paris; Tate Modern, London; and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. A center at the Zeitz MOCAA Museum in Cape Town was recently named the Roger Ballen Foundation Centre for Photography. Ballen said he hopes to help the museum develop this center to make a significant contribution to the appreciation of photography in Africa. He will appear as a keynote speaker and will be teaching a workshop as part of The Los Angeles Festival of Photography.